We often call something a parody or homage when it apes the style of a bygone era, but are there times when this descriptor could be seen as demeaning to the scale of a creation’s ambition? When the steps taken to replicate a bygone era are so extreme it’s easy to mistake a story as not merely aping but feeling plucked directly from a bygone era, are we othering a film to refer to it with such language as opposed to describing it as a creative oasis? Taroman: Expo Explosion, with its love-letter to Showa-era tokusatsu embodied in a full-throttle recreation of the era its creators love so much, left me asking this question as I jumped back in time.

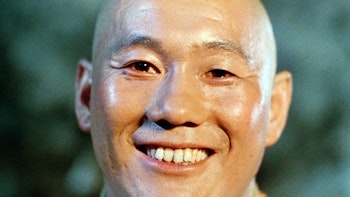

Even if you don’t know the name Taro Okamoto, you likely know his most iconic creation. For the 1970 Expo held in Osaka, Japan, the Tower of the Sun was an avant-garde structure that served as the centerpiece of the event, an imposing creation adorned with faces of various materials along its outer shell. Inside, it housed displays about the evolution of life itself, and the creation came to be an iconic symbol of the event even as the rest of the pavilions and structures were decommissioned and torn down. It was unusual, even its imposing and concrete-infused design somewhat ill-at-ease with the broader techno-futurist optimism of the rest of the show. Whatever it was, it sparked the imagination of any who saw it.

So what if it was a kaiju? Or a hero a-la Ultraman? And what if it was made in 1970? The original Taroman TV series, first broadcast in 2022 on NHK, strictly adhered to this philosophy, essentially building a lost Ultraman-esque tokusatsu series that even retained the fuzzy grain and cardboard practical sets with rubber suit heroes those series had. Merchandising even created toys that were designed with packaging and the limitations of the crude toys of the era. It was as if a time portal had been constructed to drag the hero into the modern day, without the modern reimagining you would typically expect. And it was a lot of fun!

Taroman: Expo Explosion is essentially a feature-length rendition of the story designed to emulate the films of the era. The 1970 World Expo is underway to great success, with a lot of love being given to the Tower of the Sun in particular from attendees. That’s when aliens attack, with Taroman typically jumping in to save the day alongside a hero force supporting him not dissimilar to the defense teams from Ultraman series of years past. That’s when a robot similar to the cyborg member of the team jumps in to join the fight, who reveals himself to have come from the future. They jump forward in time to see ‘Showa 100’ for themselves, but there’s more to the alien assault and the period to uncover, and even Taroman is under threat when he is taken to the future.

Compared to the 5-minute episodes of the original this is a full 100-minute film expanding the concept and having fun with the idea of embracing these analogue techniques in a modern setting. Everything about the experience of seeing the film is to make it feel, at its most modern, like watching an old reel of a classic re-released into cinemas. There’s a brief intro from one of the actors like the welcome messages once a standard to be given before films in cinemas, and the start of the film retains the fuzzy 4:3 sound-pupping retro sheen of the original TV series. With the bright colors of the costumes and clearly-artificial sets, it achieves this goal effectively, too.

Indeed, even when the team jump forward into the future, that doesn’t suddenly mean we see Taroman and crew coming to terms with the modern world. Showa 100 is a 1970s retro-futuristic image of what the year would be like, far more idyllic and quaint yet also more technologically advanced. Here the film expands to most of the full aspect ratio, but still looks like a classic film thanks to the techniques used. It’s more than just aesthetic too, with the team even going as far as to create 70s-style anthems for the movie and overdubbing most lines slightly out-of-sync, just as many films once did to overcome the lackluster audio recording capabilities on offer to studios at the time.

There’s a novelty to this experience that, regardless of your admiration for classic Showa tokusatsu and the craft involved, is refreshing to see. The carpentry and heart that went into the production is its biggest appeal, a somewhat metatextual novelty in seeing these classic techniques revived while still delivering an entertaining, childish, naive sensibility that defined the stories of the time. This will appeal to kids and those who grew up as kids in the 1970s in equal measure.

The story’s core message, touching on the power of art, community and humanity to overcome forces of power who seek to control and suppress people from being their true selves, reflects the universal messages of hope of classic Showa while embracing the love letter nature of the film’s production. The crass green screen and visible wires and artificial looks aren’t bugs but features, proof a human (and only a human) could bring Taroman to life, and it’s the support of Taroman that allows him to keep fighting for us. It’s a message befitting the film, but in an age of AI and threats to art and human creativity from market forces resonates in every paintbrush stroke background and papier-mâché monster. Even beyond this retro charm, the costumes for the villains and heroes are unique and cool in their own right, and it transports you to being a kid.

The weirdness, the ‘what the hell’ (as Taroman vocalizes repeatedly during battle), is the point. It’s not to say the film is perfect. While the team have much love for the special effects and classic tokusatsu formula and created this film out of a desire to recreate the feeling of these stories, their love for special effects worked in shorter chunks where story complexity and structure were less important than for a full film. Here, you have to know how to write a full story and not just construct costumes and fight sequences, and it’s in these quiet moments the story spins its wheels and begins to drag, unsure how to progress from moment to moment while keeping things engaging.

Yet it’s hard to be too critical when Taroman acknowledges his timeless status by ripping at the letterboxing of his film or they jump to parody interviews on his legacy today as though a revival of a classic at the age of 3. Leaving the cinema, it’s hard to believe films could still be made looking like this, and there’s nothing else like it being produced today. That alone is enough reason to jump at the first opportunity, an inevitable cult classic that plays it straight at committing to the bit of men kicking about in shiny bodysuits on miniature sets with a sense of wonder that never ages. It’s a love of nonsense and stupidity and craft, in an era that sorely needs it. I’m so glad something like this is allowed to exist.

Japanese Movie Spotlight is a monthly column highlighting new Japanese cinema releases. You can check out the full archive of the column over on Letterboxd.