It’s often easy to forget, but when Makoto Shinkai’s 2008 anime film Five Centimeters Per Second released in Japanese theaters, it also had a subtitle. This was “A Chain of Short Stories About Their Distance,” referring to the film’s structure as three distinct episodes, yet released and designed to be viewed as one continuous feature production. Indeed, when that film was being initially conceived, Shinkai initially wrote ten stories, explaining in interviews included on the original DVD that they trimmed it to the final three to avoid repetition and to ensure they had maximum impact.

Specifically, the 63-minute length of the film was designed so that the story could be viewed without interrupting or asking too much of the audience to disrupt their typical routine, while still distilling its core message for viewers to take into their daily lives moving forwards.

It falls to Yoshiyuki Okuyama, a well-respected photographer and visual artist who made his theatrical feature debut with a film similarly told in three distinct episodes, At the Bench, to adapt this tale into live-action. The choice makes sense: he’s a self-admitted fan of the original with a strong visual eye that is nonetheless distinct in the way that Shinkai’s animation is lauded for its visual detail. Yet as the trends have shifted for storytelling and the artistic desires of audiences in all industries, as they always have, it befalls upon a few red flags, so to speak.

Japanese audiences seek longer films to justify their cost - two of the biggest hits of 2025 are a 158-minute animated intro to a grand finale trilogy, and a 178-minute film about kabuki - or seek name actors whose presence nonetheless warp stories around their inclusion so the fans attending for their inclusion are satisfied. The Shinkai of Your Name transformed animation around his style, but also ushered in a more swelling and dramatic storytelling style for coming-of-age and romantic dramas that has become the expected norm for audiences. Ironically, this film has always stood as an exception to this type of grandiose finale amongst his career. Adaptation with the times is inevitable, but maintaining the original's poetic ambiguity is an unfortunate impossibility in these more frantic times.

Takaki Tono is approaching 30 years old, but can't open up to those close to him. He's distant even to his long-term romantic partner from work, and aside from throwing himself into his programming, he doesn’t give others a moment to see the real him. Occasionally, memories of the past come back to him, reminding him of the girl named Akari Shinohara he befriended in middle school after she, like him, transferred to a new school. A time where they became fast friends, perhaps more, until Akari was suddenly forced to move away.

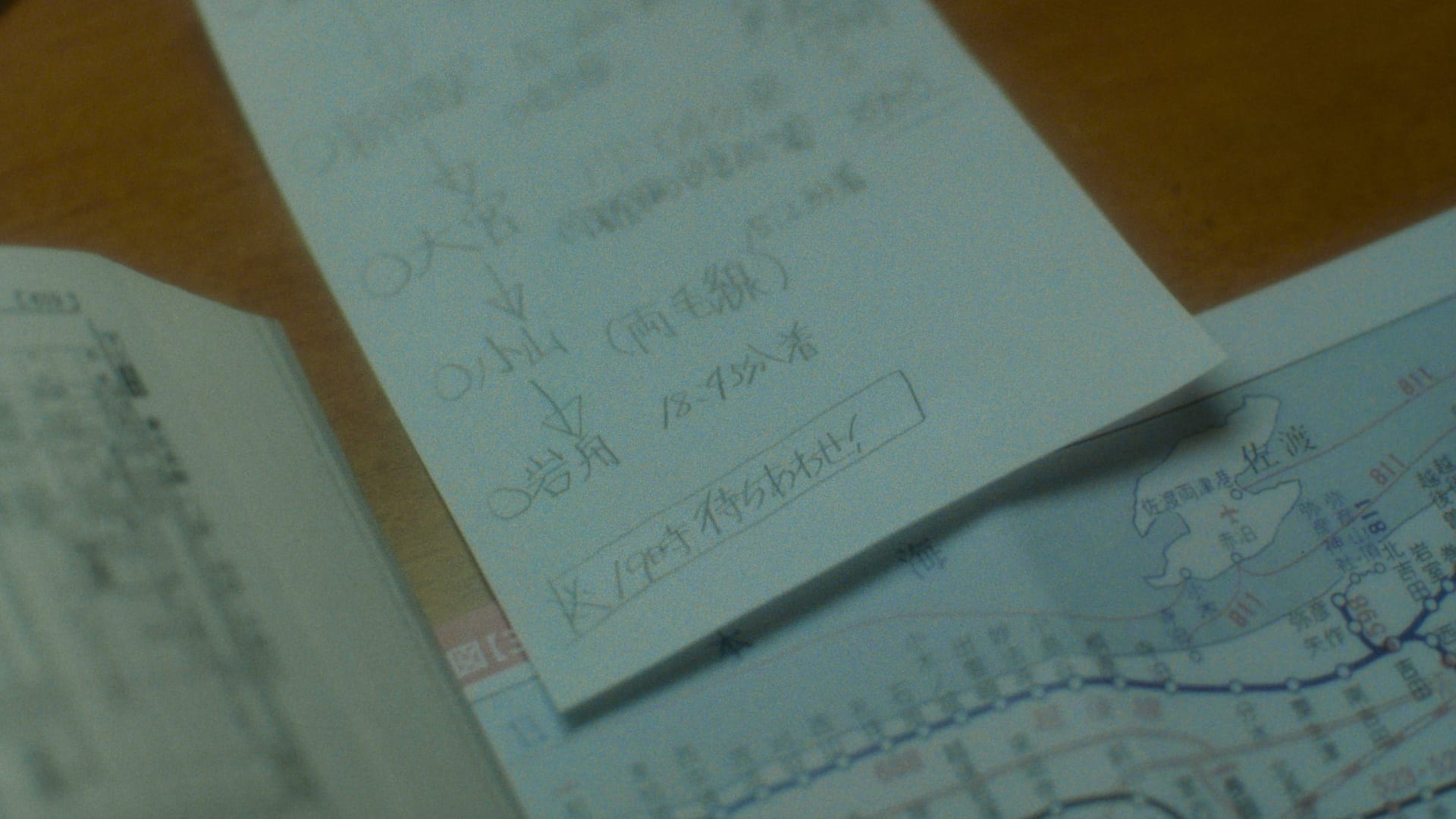

The film jumps between Takaki’s adult life (performed by SixTONES’ Hokuto Matsumura who also starred in Kyrie and even Shinkai’s Suzume), his middle school days (Haruto Ueda) and his high school days far from Tokyo when he, too, is forced to move (Yuzu Aoki). In a reversal of the typical structure for this story, however, we begin with Takaki lost and forlorn as an adult, the story told in flashbacks. Takaki's younger self was lively, with a love for space, expressing shared interests with a young Akari (Nao Shiroyama). When comparing that kid, so excited by the 1991 shuttle launched into space with recordings of humanity for aliens to discover, to the lost adult, especially when adult Akari (Mitsuki Takahata) is thriving as a bookstore clerk, it’s hard not to wonder how the past is weighing on Takaki.

This 1991 shuttle launch is referenced heavily, serving as a metaphor for the story to be viewed within. This capsule was shot into space with no guarantee it would find anything, yet it nonetheless professed love and a desire to connect. It was sent with hope. It couldn’t be further away from what Takaki is feeling as his long-term relationship falls apart because she can't recognize his heart growing any closer. The shuttle constantly brought up during the adult segments of the film, not just because the 2009 timeframe retained from the original is when this shuttle would have completed its initially-planned mission. The planetarium he gets a new start as a programmer gives a chance to recontextualize the past in the context of this mission.

If adult life feels prominent in this new Five Centimeters Per Second, it's because this short epilogue now encompasses over half the film. It was always core to espousing this story's core message - at times relationships fail without reason or blame, and that regret can eat at you unless you accept it made you the person you are now, and move forwards embracing the strength it brought. There isn't always answers, it’s not always neat like the movies say, but that’s fine.

The reasons for extending this segment are obvious: Matsumura, certainly a talented actor as his star turns in numerous films including All The Long Nights prove, is too big a name to minimize his importance, especially if you want him on a poster to promote the film. Yet even if his performance itself is good, making him the central force for which the story revolves replaces liminal storytelling and poetic monologues exploring inner thoughts via written letter for something more simplistic and traditional and easy for audiences, but far less emotionally resonant.

New storylines seek to emphasize the power of reflection on the past to find peace with the present and the way those relationships built everyone, from Kanae to Akari to Takaki, yet because of the outsized amount of time spent with the characters as adults this is done without actually spending the time building those relationships. By the time we reach the finale, the story disintegrates into the equivalent of characters turning to the camera to state the moral of self-reflection and growth, accepting that life moves on as the stars shine and the petals fall. No need for audiences to reach that conclusion themselves.

Five Centimeters Per Second is easily the most visually-stunning Japanese film of the year, building on At The Bench’s use of traditional film stock to give the film a nostalgic, grain-heavy, bloom-infused nostalgia that roots and elevates the melancholy of the story. As should be expected from this director considering his background, his scene composition is impeccable, posing each scene like a painting without letting the composition distract from the characters. It, too, creates a dreamlike feel to the film, framing moments like memories without removing them from reality.. The acting, especially from the younger cast, is second-to-none.

Yet it’s all this that makes these flaws in the script, the dumbing down of the story and undercooked expansion of moments for Takaki as an adult that only diminish rather than enhance the core ideas, that much more apparent. While it’s unfair to solely judge a film on how it compares to the original, it’s unavoidable when the nature of a remake means it will always be viewed in relation to its predecessor.

For all the argument has been made that Shinkai’s storytelling and animation style have led some to proclaim his stories would befit live-action better than anime, this film is an argument to the contrary, especially in the current state of Japanese filmmaking. The economics of filmmaking and the realities of live-action pitching it closer to reality makes this a story that can’t naturally make the jump to this new medium without sacrificing what made it so great in the first place. To bring in audiences you must prioritize one actor, yet doing sacrifices the structure of the story in the process when animation can mask it all.

Even with a highly-talented director with a grand future in Japanese film and a strong cast, it’s hard not to see economic reality and oversimplification ripping the soul from Five Centimeters Per Second. Even shots directly calling back to the original film feel devoid of their intent in this new form. Rather than the graceful floating of a sakura petal, this film feels more like the inelegant thud of reality crushing hopes this could live up to the strengths of the original creation.