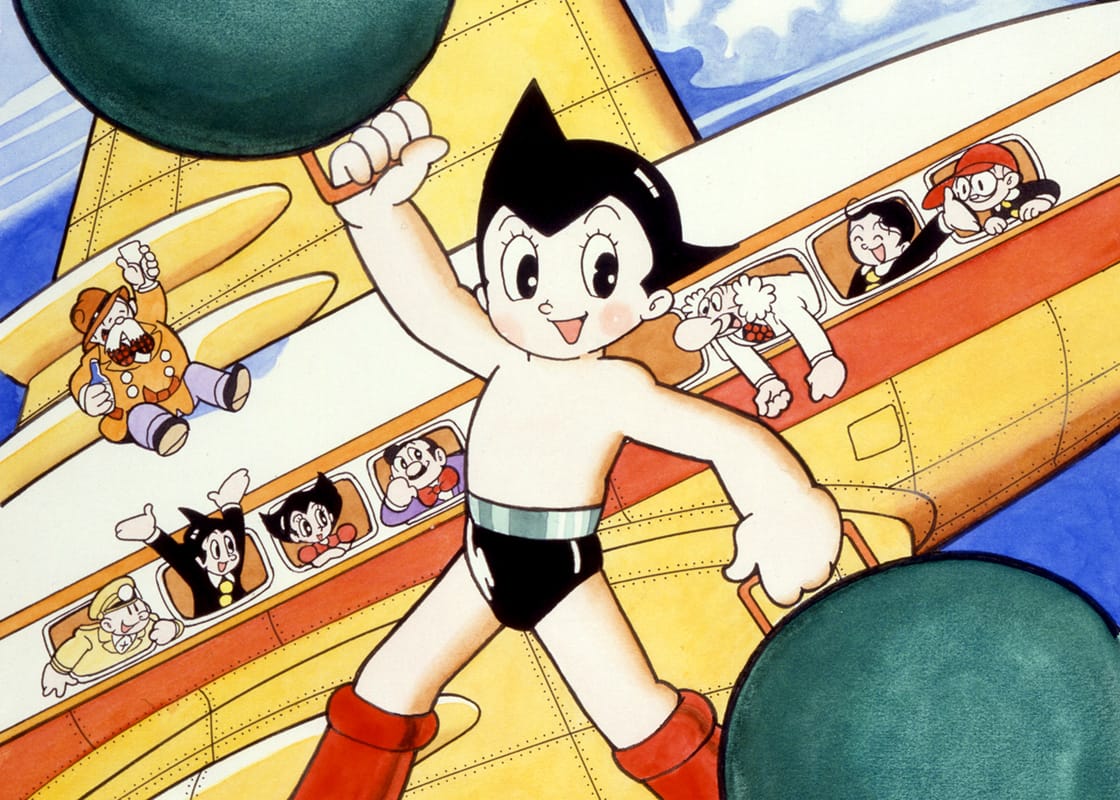

When pondering the question of why comics had become so popular in Japan, the Asahi Shimbun once remarked that “Japan had Osamu Tezuka, while other countries did not.” Even now, Tezuka’s name is so closely associated with the medium that he is often called the “God of Manga,” but the reasons for this are rarely understood. Perhaps no single series offers a better explanation than Astro Boy.

Beginning in 1952 and continuing in various forms until 1981, Astro Boy is Tezuka’s best-selling and most famous work. This is somewhat surprising when you consider the sheer amount of manga he put out over the course of his career: the Osamu Tezuka Complete Collection, published by Kobunsha, sits at a whopping 200 volumes. At least part of this is due to all of the different adaptations that have cropped up over the years, starting in 1961 with the original TV anime all the way up until the present day with such spin-offs as Atom: The Beginning and Pluto, but the influence of the original series cannot be understated.

As the first part of this new series of articles exploring some of Japan’s most important and influential manga, nothing seemed more apt than the series that arguably started it all. From the proliferation of manga into the cultural mainstream to the way that adaptations are made today, almost everything can be traced back to Astro Boy in some shape or form. In many ways, this is Atom’s world… we’re just living in it.

Diamond in the Rough

To truly grasp the importance and influence of the original Astro Boy manga, it is essential to first understand the circumstances in which it was created. At least to a certain extent, all art is both limited by and allowed for by the specific period it inhabits: this goes just as much for the kind of stories that can be made as it does what audiences resonate with. In Astro Boy’s case, you could say that it was in the right place at the right time.

Back in 1952, the manga industry was not the behemoth it was today. A few magazines existed on a national level, but it was still a relatively minor form of entertainment mainly meant for young children and largely ignored by the cultural mainstream. In fact, the industry was so underdeveloped that many of the very first manga magazines were mainly filled with illustrated prose, including the place where Astro Boy was first serialized.

As the young editor-in-chief of the newly created Shonen magazine, Takeshi Kanai wanted a new manga series that would give Japanese children “hope and courage” following the disastrous events of World War 2. In this respect, the effects of the war cannot be understated: not only were many communities still rebuilding from the physical fallout of the conflict, the country had emerged from a decade of oppressive ideology centered around militarism and emperor worship into a period of relative creative freedom. Entertainment that both captured the spirit of the time and presented a strong break from the past was proving increasingly popular, most especially science fiction stories in the American style.

For Kanai and the other editors of Shonen, no one seemed better suited to this task than the young Osamu Tezuka. What initially caught their eye was his work on several early akahon titles: these were cheaply printed, self-contained stories sold primarily to children at candy stores, but Tezuka’s talents still managed to shine through despite the limited format. Based on a story by Shichima Sakai, New Treasure Island from 1947 proved a particular success due to its revolutionary visual presentation that gave the reader the sensation of watching an animated movie.

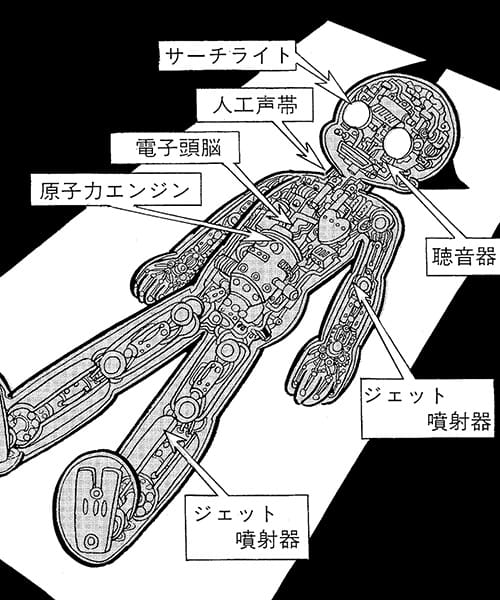

Although Kanai and his peers had high hopes for Tezuka, it must be said that the initial iteration of Astro Boy proved to be something of a failure. The first work that Tezuka actually published in Shonen was called Ambassador Atom: the fantastical tale of a fictional country in the near future that had managed to harness the power of nuclear energy for peaceful purposes, including the creation of advanced humanoid robots. While it shared some basic features with Tezuka’s later hit, it ultimately proved to be far too complicated and was canceled after just one year.

That being said, Shonen didn’t give up on Tezuka. Recognizing that the robot character called Atom introduced halfway through the story proved to be the most popular among younger readers, Kanai suggested to Tezuka that he retool the series to make him into the protagonist. It is worth noting that Tezuka was initially against the idea as he thought that it would be too difficult to make a robot into the star, but then the idea came up to give Atom more human qualities: this would, inadvertently, go on to be one of many reasons for Astro Boy’s success.

Blazing a Trail

Even if Astro Boy was a product of unique circumstances at the time, the way that it thrilled and entertained audiences was entirely down to Tezuka’s unique visual and storytelling style. In particular, readers found themselves drawn to the sheer amount of ideas crammed into each and every page: one minute Atom would be fighting other robots and monsters from outer space, the next he would be struggling with his own quasi-humanity and how to relate to others. The popular perception of Astro Boy nowadays is somewhat happy-go-lucky, but Tezuka’s love of Russian literature, Japanese mystery stories and Hollywood movies shines through all the same.

In many ways, Astro Boy was responsible for propelling manga from a niche medium with a limited readership to a popular pastime on a national scale. While there were obviously many other series published at the time, none of them managed to achieve that same kind of popularity or reverence across a broad demographic, nor spawn as many subsequent adaptations. An advertisement for the series’ collected volumes in a 1964 edition of the Tokyo Shimbun carried testimonials from a novelist, a university professor, and even a sumo wrestler, all of whom unabashedly declared their love for the series.

Both out of reverence for Tezuka and in an attempt to capture some of Astro Boy’s success for themselves, artists around the country borrowed, copied, and paid homage to several aspects of the series in their own work. Perhaps the most famous example of this is Tezuka’s art style: while a childhood spent watching Disney animation had influenced Tezuka to draw characters with large eyes and rounded bodies, this ironically became the “Tezuka style” in Japan and began to proliferate across the industry. Of course, the “manga eye” has become so common that it is now practically a symbol for the industry and one of the most striking ways it sets itself apart from other comics in other countries.

Despite finding himself at the head of a medium-defining series with Astro Boy, Tezuka didn’t stop turning down job offers. In fact, Astro Boy began serialization concurrently with Jungle Emperor Leo and continued all the way through Tezuka’s career alongside countless other works until 1981, meaning that he was forced to find ways to work and draw efficiently. The solution he found was to divide the labor of manga production between himself and a team of helpers: Tezuka would come up with the story and pencil the characters before passing background work as well as other miscellaneous finishing touches to others, thus creating the modern system of assistants that is still used today.

Far from just pioneering this system, many of the artists employed in Tezuka’s framework would go on to produce medium-defining works all by themselves. These included such hallowed names as Fujio Akatsuka (Osomatsu-kun), Fujiko F. Fujio (Doraemon), Leiji Matsumoto (Space Battleship Yamato), and Shotaro Ishinomori (Kamen Rider), among others. All of the ways that Tezuka both influenced them and shaped their future career is another article in and of itself, but suffice it to say that it was an formative experience.

On a final note, publishers capitalized on Astro Boy’s tremendous success to not only sell copies of the series’ collected volumes, but also a wide range of related goods and merchandise. To be fair, most of these items came onto the market in conjunction with the anime, but the crucial thing is that Tezuka and his company took a royalty every time something was sold: this included everything from candy and toys to clothes and skis for children. As a result, a harmonious relationship was created between the original work and related items, both functioning as a source of revenue and a way to advertise the series in a way that echoes the multimedia empires of today.

Revolution in Motion

While the focus of this series is primarily on important and influential manga, any discussion of Astro Boy would be incomplete without recognizing its extraordinary impact on the world of Japanese animation. Much like the ideas explored in the previous section, the creation of the Astro Boy anime set several important precedents in production and distribution that still exist today. The question of whether this legacy is a positive one, however, remains up for debate.

As the first manga series to achieve nationwide popularity in the media mainstream, the mere fact that Astro Boy was also the first manga to be made into an animated television series is nothing short of extraordinary. What’s even more extraordinary is the fact that its original creator was directly involved: Tezuka founded the studio that produced the adaptation, although his contribution to the project waned the longer it went on. This particular aspect of the production isn’t one that would be repeated for subsequent works of Japanese animation, but plenty of others would be.

Given the relatively limited level of technology at the time, the prospect of producing 24 minutes of animation every week for three years was nothing short of monumental. Following in the footsteps of Walt Disney and other foreign works, most animation produced in Japan up until this point had been extremely labor intensive and time consuming as animators attempted to achieve smooth motion and realistic detail through the use of key frames, but the demands of the Astro Boy project forced Tezuka Productions to find a different approach. What they eventually settled on was the use of limited animation, allowing them to produce episodes at a much faster rate with a smaller team.

Although the introduction of computer-generated graphics and digital production has changed the look of Japanese animation today, the limited animation approach still remains. If you watch an episode of the original Astro Boy anime, you’ll be shocked to see many of the same time-saving techniques used today: zooming, still shots, recycled shots, and only animating characters' mouths when they talk. While this has allowed the Japanese animation industry to flourish and ultimately produce far more works than many other industries around the world, many have subsequently criticized the precedent this set for low budgets and low wages, with Hayao Miyazaki once describing it as a “curse” that still affects the industry today.

Even with the time saved by the limited animation approach, the Astro Boy anime project still required a huge team to make it happen. As a result, it drew in countless people from across the entire industry, including some figures that would go on to become giants of animation in and of themselves: Eiichi Yamamoto (Belladonna of Sadness), Rin Taro (Galaxy Express 999), as well as Yoshiyuki Tomino (Mobile Suit Gundam), all of whom served as episode directors. Much like the gilded list of talents who served as Tezuka’s assistants on the original manga, who knows how they might have turned out without this experience?

Finally, it is worth noting that Astro Boy also holds the distinction of being the very first animated series from Japan to be licensed and broadcast overseas. To a certain extent, this makes sense as Astro Boy was also the first animated series ever to be made for television in Japan, but this cemented the synergy between domestic production and foreign licensing right from the very beginning. Considering that sales outside of Japan overtook the domestic market for the second time since 2002 earlier this year, this dynamic has only become more important as of late.

Boy of the Future

Given that the focus of this article has been largely on the importance and influence of the original Astro Boy manga, there hasn’t been much opportunity to talk about the actual stories. This is a shame as so many of them are so captivating and worthy of discussion all by themselves: some of my favorites include “Gone with the Snow” and “His Highness Deadcross”, as well as “The Artificial Sun”, but no matter. Put simply, there’s no better way to discover the timeless nature of Tezuka’s masterpiece than to read it for yourself.

Aside from raw sales numbers, perhaps the most striking example of Astro Boy’s continued capacity to captivate audiences and creators alike is the sheer amount of adaptations that have been produced over the years. These include the original black and white anime produced by Tezuka Productions in 1961, a full color remake in 1980, as well as a 3D animated film in 2009. Of course, an adaptation of Naoki Urasawa’s Pluto manga also finally released a couple of years ago, wowing audiences and surprising many that something so serious could be gleaned from a manga that seems so innocent.

The perception of Astro Boy as a fairly inconsequential series with no appeal beyond younger audiences is largely due to the first Tezuka Productions anime, which presented a more triumphant take on the source material through its original stories. Even so, early stories such as “Franken” dealt with such complex themes as racial discrimination, going as far as to connect the plight of fictional robots with the very real contemporary situation facing African Americans in the United States. What’s more, the fact that the first anime only ran for two years between 1961 and 1963 means that it missed out on the chance to adapt more serious stories that were influenced by the rise of gekiga: these include the controversial “Blue Knight” that saw Atom forced to agree with the antagonist’s motives and eventually blown to pieces by the end.

Far from just an exercise in historical research, Astro Boy deserves to be rediscovered by modern audiences both because of its influence and value as a piece of thought-provoking entertainment. Atom may have reshaped the world in his image, but his soul still burns bright today. Look around: you can’t miss it.

You can read Astro Boy in English via Dark Horse Comics. For further reading, check out The Astro Boy Essays by Fredrick L. Schodt.