Japan is often thought of as a society free from political strife. This certainly might seem to be the case when you consider that neighboring countries China and Korea experienced social upheaval, civil wars, and even wholescale revolutions throughout the 20th century, but this couldn’t be further from the truth. Not only does Japan have a rich history of counterculture, manga such as Ashita no Joe can intersect with it in fascinating ways.

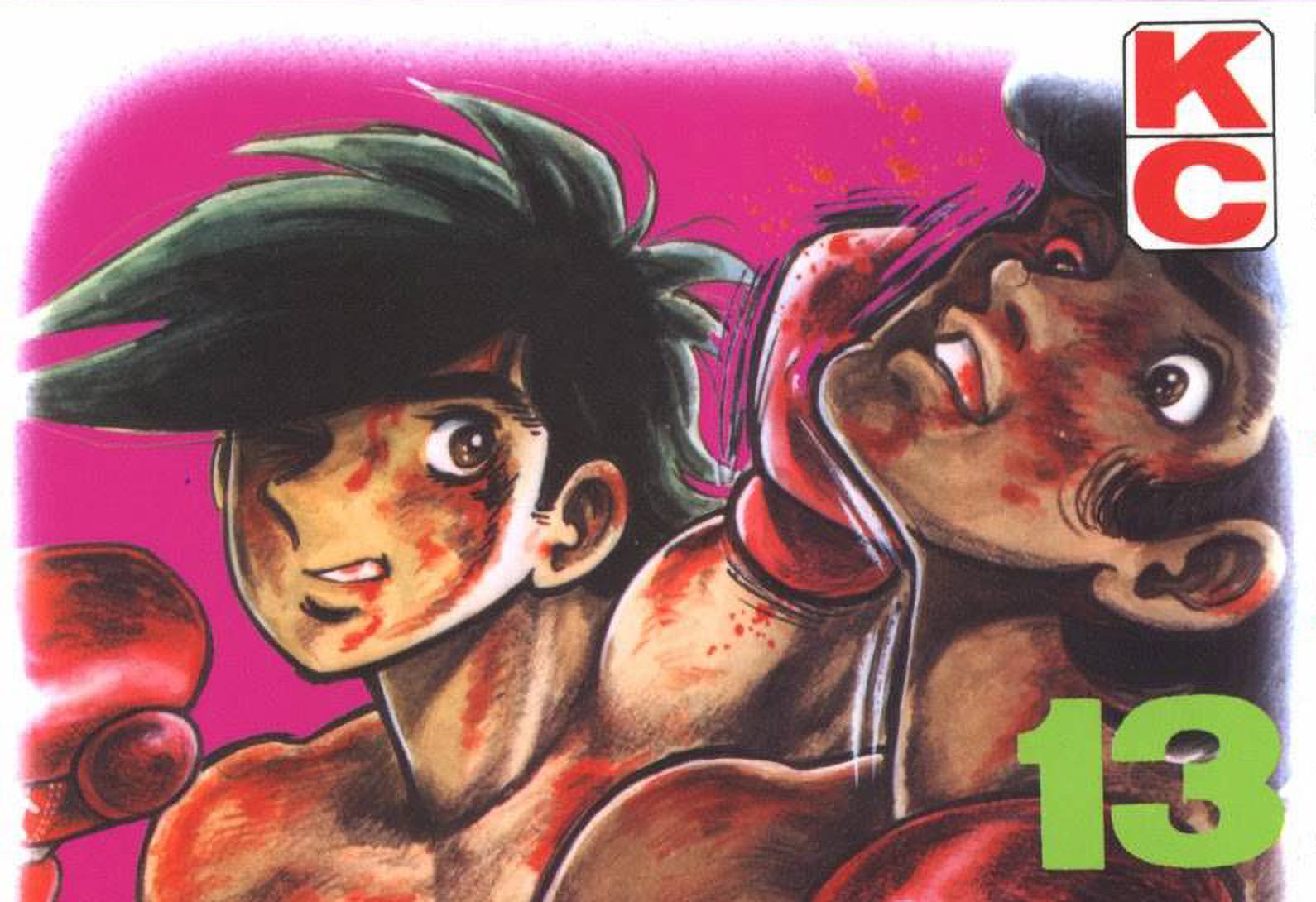

Penned by Tetsuya Chiba and based on a story by Asao Takamori, Ashita no Joe is widely regarded in Japan as one of the most important and influential manga of all time. You can find not one, but two different statues of the titular protagonist in Tokyo alone: one in Nerima as part of the Oizumi Anime Gate project, the other in Taito where part of the series is set. References to iconic moments from the story also crop up regularly across popular culture in works as diverse as Tengen Toppa Gurren Lagann and Daily Lives of High School Boys.

Nevertheless, recognition of the series overseas has always been severely hampered by problems of availability. Kodansha finally began an English publication for the first time last year, but this means that readers outside of Japan are almost 60 years late to the party. What’s more, much of Ashita no Joe’s legacy stems from the events associated with it as well as the story within: understanding why it is important first means understanding the role it played at the time… including all of the shocking details.

Red Right Hand

The immediate postwar period was not a peaceful time in Japan. Despite the growth of industry and the middle class as part of the “economic miracle,” political disagreements raged with regards to the direction of the country and what role it should play on the global stage. For many, the promises of the Allied Occupation for liberal reform and democratization quickly seemed to dissipate against cold hard reality, particularly when the Korean War broke out in 1950.

Although labor unions and other organizations such as the Japanese Communist Party were active during this period, young people and students emerged as particularly militant voices. Having lived through and even served in the war under some circumstances, they tended to hold strong anti-war sentiments that clashed with the state’s subservience to western imperialism, along with a desire for academic freedom. Their resistance started as early as September 1945, just as American forces began to arrive on the island, with a student strike against authoritarianism at what would go on to become Ibaraki University.

Similar strikes then cropped up in different campuses around the country, eventually leading to the formation of the All-Japan Federation of Student Self-Government Associations in 1948. Commonly known as the Zengakuren, this national body brought together otherwise disparate student bodies into one organization, effectively transforming universities and colleges into interlinked centers of struggle. What’s more, the Japanese Communist Party played a key role in the foundation of the Zengakuren, although the relationship between the two institutions was never exactly harmonious.

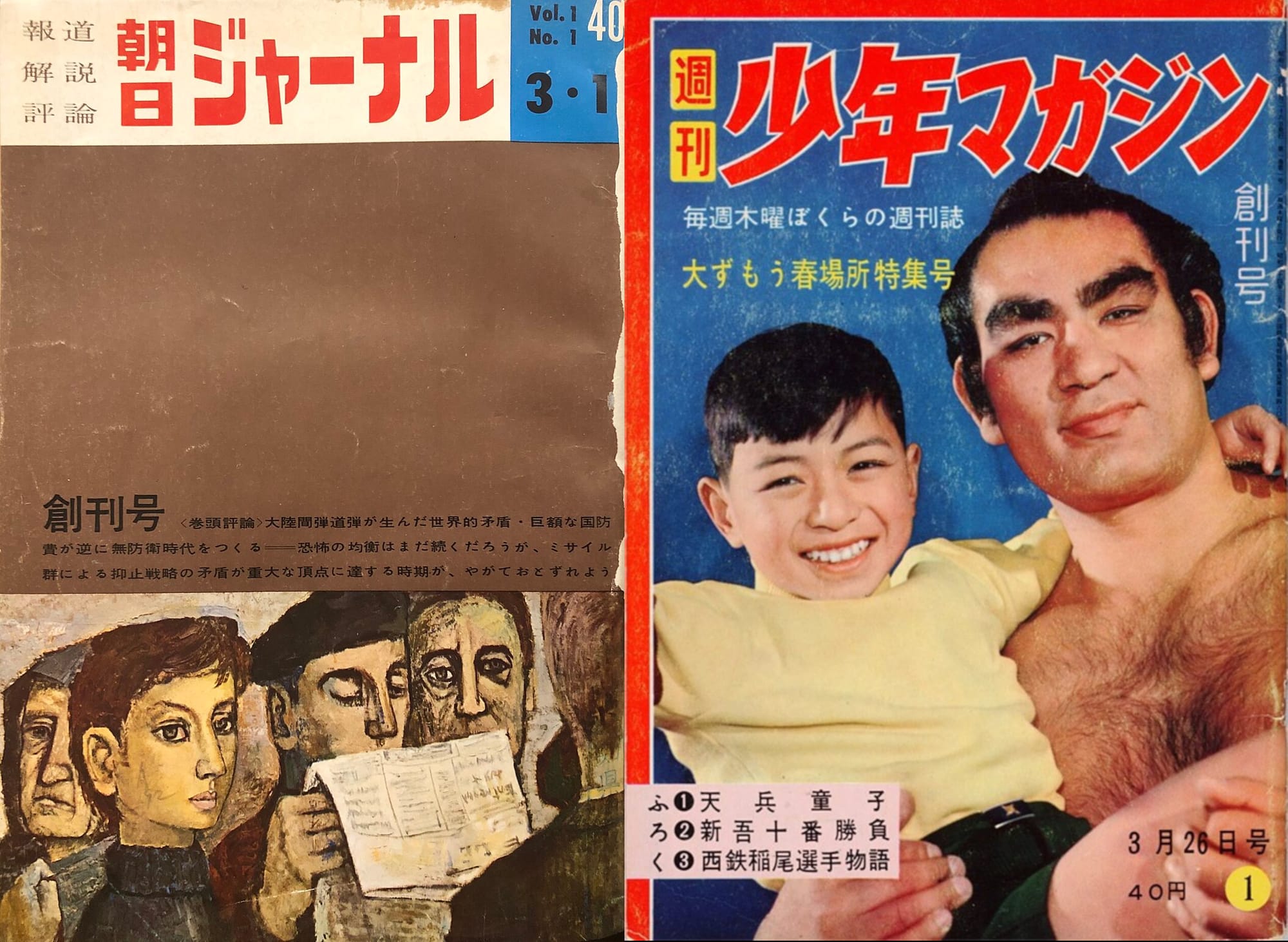

While the Zengakuren exercised a sizable influence over the youth, one phrase that is often thrown around by historians with regard to 1960s counterculture is “Journal in the left hand, Magazine in the right.” This supposedly originated from a piece written for the Waseda University newspaper in 1969, but more broadly indicates the strong youth readership for two publications that just so happened to go on sale on the same day: the Asahi Journal and Weekly Shonen Magazine. Despite being aimed at completely different demographics, both served important roles in the events to come.

With the stated mission to “inform, explain, critique”, the Asahi Journal was the intellectual backbone of counterculture throughout the 1960s and 1970s. Formed in 1959 alongside Asahi Graph and Weekly Asahi during a publishing boom by the Asahi Shimbun Company, Journal quickly became a touching point for more left-leaning adult readers due to its initial focus on stories related to the Vietnam War and the US-Japan Security Treaty. In a rare achievement for a weekly publication, the 1960 issue reporting on the death of 20 year old student Michiko Kanba following a clash with police at an anti-Treaty demonstration completely sold out, triggering a round of hasty reprints.

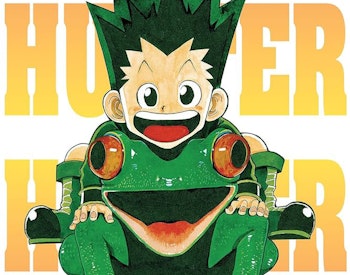

Weekly Shonen Magazine, on the other hand, was a manga magazine meant for children. Kodansha’s flagship publication is now understood to appeal mainly to high schoolers and university students, but the popular perception at the time lumped it together with all of the other weekly magazines as a juvenile piece of entertainment. That didn’t stop older readers from consuming and relating to the stories contained within, however, chief among them being Ashita no Joe.

We are Joe

In 1970, nine members of the Red Army Faction of the Communist League boarded a Japan Airlines flight from Tokyo to Fukuoka. Also known as The Bund, the Communist League was a splinter group within the warring Zengakuren that opposed both the Japanese Communist Party and the Soviet Union, operating under the slogan “anti-imperialism, anti-Stalinism.” The Red Army Faction, on the other hand, was a splinter group within the splinter group that believed that only violent guerilla tactics could carry through the revolution at home.

Armed with a katana, Red Army Faction member Takamaro Tamiya screamed out “We are Joe!” before beginning to hijack the flight with over 100 passengers on board. The group’s original plan was to head to Cuba, where they would receive training from communist forces, but the crew quickly informed them that the aircraft did not have enough fuel to make such a journey. Settling instead for North Korea, all nine Bund members made the journey to Pyongyang where they still live today: the rest of the hostages, including the Vice Minister for Transport, were released two days later.

Not every fan of Ashita no Joe was a violent communist guerilla, but the invocation of Joe’s name at the beginning of such a shocking incident does speak to the stranglehold that the series had over radicals at the time. Why did Tamiya choose to dedicate this fateful moment to a fictional character? His flight to North Korea with the other Red Army Faction members and subsequent death in 1995 meant that no one was ever able to ask, but the reasons can be deduced.

First of all, Joe himself was an inherently revolutionary character. As a wanderer from the slums of Doya-machi with no prior background or familial ties, he literally emerged from nothing to completely upend the entire boxing world, challenging all norms and preconceptions along the way. What’s more, his attitude towards society was subversive to say the least: he never cared much for the rules, even ending up at a youth correctional facility in the early part of the story where he would meet his fated rival, Rikiishi Toru.

That being said, Joe’s situation changed dramatically as the series went on. His victories in the ring resulted in considerable material wealth and many opportunities to rub elbows with the highest echelons of society, but only bouts against stronger and stronger opponents brought him any satisfaction. In this sense, Joe’s own attitude towards material success mirrored the alienation that radicals felt towards modern society: they saw themselves in Joe’s quest for self-actualization beyond the established framework, even if the results were self-destructive.

If Joe’s revolutionary nature and attitude towards modern society fit the mould of contemporary counterculture, then the setting of the story also reflected its ideal class character. Although Doya-machi is technically a fictional place, it drew heavy inspiration from the real neighborhood of Sanya in Taito City: a now-defunct area that contained many cheap lodging houses for day laborers and travellers. Moreover, ordinary workers from the area make up a large part of the series’ cast of colorful characters, making it into a bonafide slice of proletarian life.

Nothing but Ashes

Somewhat ironically, the heyday of Ashita no Joe came about just as the student movement was beginning to fade. The symbolic defeat of the Zengakuren is usually given as the end of the Tokyo University occupation in 1969, but the reality is that momentum had run out long ago: research has suggested that no more than 20% of students were involved in similar struggles at the time, meaning that only a small minority of dedicated activists remained. Further momentum was lost in 1970 following the renewal of the US-Japan Security Treaty despite nationwide demonstrations.

In fact, the twin failures of the occupation movement and the anti-Treaty protests were what led to the split within the Communist League that brought about the Red Army Faction, thus bringing about the Japan Airlines hijacking incident. With this in mind, perhaps Tamiya’s utterance of “We are Joe!” was more of an affirmation than anything else: a reminder to his comrades of what they were supposed to be in spite of the disappointing reality. Indeed, Tamiya is reported to have also said “Let’s make one last thing clear” before the famous line, highlighting his desire to clarify why the Red Army Faction were doing what they were doing.

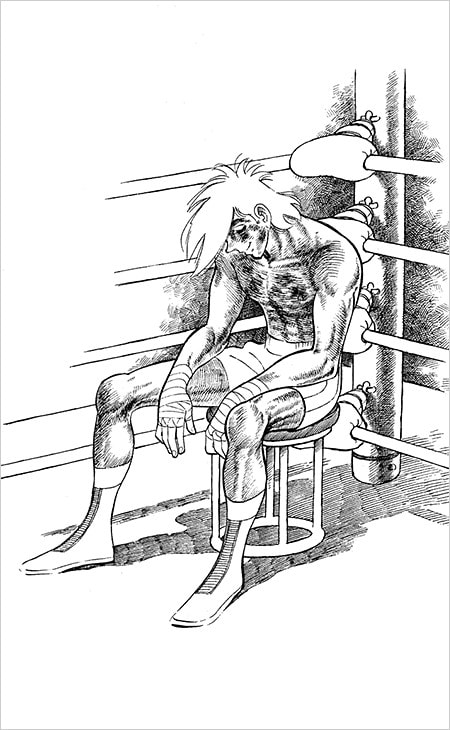

Alongside the cross counter, one of the symbols of Ashita no Joe that has persisted in popular culture throughout the years is its ending. Having given his all in the bout against bantamweight world champion Jose Mendoza, Joe is depicted as “burnt out” in his corner of the ring in between rounds, sitting on a stool with his arms limp by his side. What makes the final panel especially haunting is the fact that Joe has a smile on his face: despite losing, he is ultimately satisfied with his performance and the life he chose to live.

Even now, the question of whether or not Joe had passed away at that moment is hotly debated. Tetsuya Chiba has repeatedly stressed in multiple interviews that he never intended for the scene to be taken that way, but the lack of clarity within the narrative has caused that to become the popular conception. In fact, Chiba actually changed the ending to be more ambiguous: the initial story outline he received from Takamori contained a scene depicting Joe living out the rest of his days at the Shiraki estate under the watchful eye of his on and off love interest, Youko, making it clear that he lived on.

Rather than the question of Joe’s death, however, what’s arguably more important about the series’ ending is the tragedy that it invokes. As mentioned, Joe is never able to enjoy the fruits of his success in the second half of the series and only lives for the thrill of his next fight, ending up with punch drunk syndrome in the process. Before the fateful match against Jose, Youko even begs him not to fight, but Joe responds with the chilling line: “The strongest man in the world is waiting for me in that ring… that’s why I have to go.”

Like Joe, were the student radicals of the time able to go out with a smile on their faces, or were they simply unable to move on? Beyond the hijacking group, other remnants of the Communist League staged much more brutal events in the 1970s that shocked the public at at large: one group retreated to the mountains north of Tokyo and engaged in a violent standoff with thousands of riot police for multiple days, while another carried out a massacre of civilians at Lod Airport outside of Tel Aviv in Israel. When the only living perpetrator of the second atrocity was asked why he did it, he simply replied that he was doing his “duty as a soldier of the revolution.”

Fighting for Tomorrow

It goes without saying that the situation in Japan is very different today… or is it? Just three years ago, former Prime Minister Shinzo Abe was assassinated in broad daylight by a disgruntled citizen. An attempt on then-Prime Minister Fumio Kishida’s life came not long after: this shows that political violence is still very much a part of Japanese life, even if its scale and regularity have decreased dramatically over the years.

Opinion also seems split on the direction of the country and what role it should play on the world stage. Successive leaders have tried and failed to overcome both internal division and public opposition to the idea of repealing Japan’s pacifist constitution, with Kisihida eventually settling for a massive boost in defence spending before stepping down in 2024. Aggressive tariffs have also brought Japan’s long-standing alliance with the United States into question, prompting an unprecedented trilateral conference with China and South Korea to try and strengthen trade ties.

What’s more, the youth are beginning to move back into action once again. Ever since the outbreak of the war between Israel and Palestine back in 2023, pro-Palestinian rallies have been held outside of Shibuya Station almost every week, spearheaded by high schoolers and university students. This is significant as the violence of the Zengakuren highlighted above had largely discredited political activism for subsequent generations, but perhaps both memory and knowledge of these atrocities have faded enough with time to lay the foundations for a new struggle.

In this sense, there is no better time than the present to rediscover Ashita no Joe and its rich heritage. We could all stand to learn a thing or two from Joe’s relentless determination to overcome humble beginnings and achieve great things, but we should also remember that his tale was as much of a tragedy as it was a success story. Similarly, while his revolutionary spirit should serve to bolster the struggles of today, we should also be careful not to repeat the mistakes of the past: more specifically, the inability to adopt proper tactics based on the general mood of society.

There is a very good reason why Joe is “Tomorrow’s Joe” above all else. Just as the character was always moving forward and looking to the future, the series’ legacy will keep evolving as it is rediscovered by subsequent generations. What will Ashita no Joe mean in 50 years, or even 100? Only time will tell, but it will surely be a story worth telling.

You can read Ashita no Joe in English via Kodansha under the title Ashita no Joe: Fighting for Tomorrow. For further reading on Japanese counterculture, please check out William Andrews’ excellent Dissenting Japan: A History of Japanese Radicalism and Counterculture from 1945 to Fukushima via Hurst & Co.