Masamune Shirow is known most notably for his work on Ghost in the Shell and Appleseed, and many will quickly remark on how these works alone influenced science fiction and its creators. The Wachowski Sisters and James Cameron have cited his work as influential, and the original anime adaptation alongside the work of him and those he inspired undoubtedly stand as amongst the most iconic stories in the genre. What’s less-known, however, is just how much Shirow changed the course of science fiction in his home country of Japan also, with the broad influences on his work allowing him to approach his work from a new perspective reflecting both these ideas and politics of the time to create something truly fresh that shifted the course of the genre in the country.

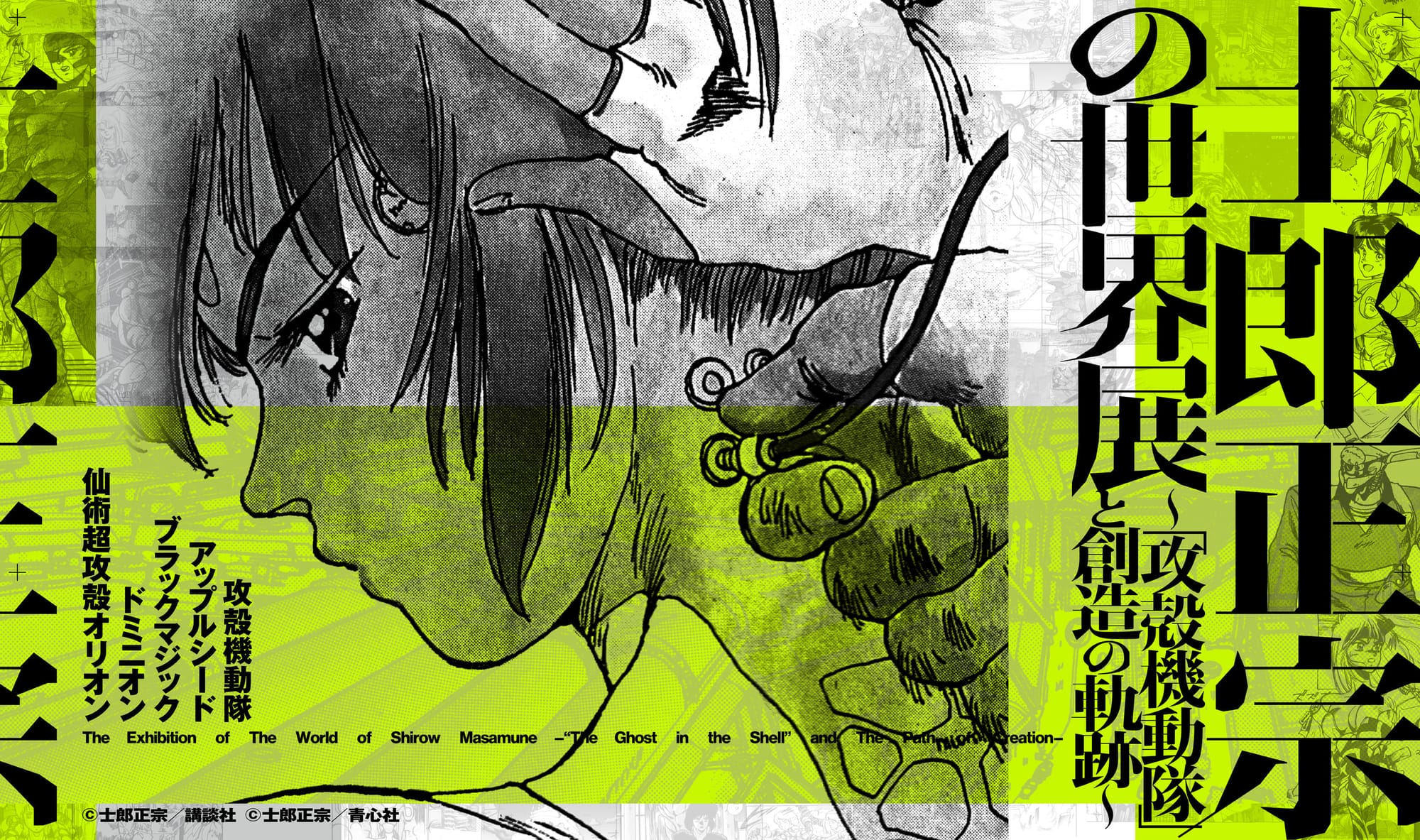

At the Setagaya Literature Center on the outskirts of Tokyo, an ongoing exhibit seeks to shine a light on the career of Shirow as part of an event not just marking 30 years of the institute itself, but 30 years of the Ghost in the Shell anime and 40 years since the initial publication of Appleseed. Inside its walls are an open-plan exhibit centered on allowing attendees to freely flit in and out of a retrospective of large chunks of the creator’s career until the 2000s as well as his creative process in both analogue and digital mediums, punctuated by both original and copies of manuscripts from a huge selection of his works. While obviously a lot of space is dedicated to his most well-known series, the exhibit is not beholden to its overbearing influence, seeking instead to capture the man’s process and influences.

And it’s these influences most worth noting. While not to say that Japan lacked science fiction prior to the 1950s - Osamu Tezuka found success with series like Metropolis in the 1940s, and you can trace the roots of the genre in the country to the opening of Japan in the years leading to the Meiji Restoration - it’s concurrent to the explosion of kaiju cinema with the original Godzilla film that more mainstream genres begun to emerge thanks to fanzines like Uchujin and Hayakawa’s SF Magazine. The first successful commercial Japanese science fiction magazine, this publication facilitated both home-grown Japanese writers as well as translated fiction from abroad, and ushered in further events and publications through the 1960s as more works emerged, most famously Astro Boy.

Science fiction at this time was, thus, an imagination of an idealized and peaceful future reflective of the country’s shift away from wartime and an intent to consider the problems of the country to an idealized future at a time the country was rebuilding. It’s why you had stories imagining rebuilt and idealized societies like this or hero characters such as Ultraman, though that doesn’t mean there weren’t works that considered the country’s potential collapse or more dystopian examples. Some of the most famous science fiction stories of the era are ones like Japan Sinks or Inter Ice-Age 4.

Yet it’s here where we notice a divergence in the ways Shirow approached the genre and many of his contemporaries. As anime and manga grew in popularity you saw a divergence in the visual and literary fields of science fiction, with works such as Macross and Gundam depicting future societies with giant robots and weaponry for futuristic wars in space whose conflicts reflected the racial and societal divides of our modern societies, and works like Space Battleship Yamato exploring the nature of humanity against the backdrop of a decaying planet in the heart of deep space.

One thing rarely depicted in science fiction at the time, however, was how the advances in techs and the introduction of robots replacing humans at tasks and existing among us could change the relationships between people and even between human and robots. Could human relationships with robots exist? Could humanity be further augmented by technology? As this technology becomes commonplace, how could it change things we take as standard in how we perceive the world, how we live our lives, or even the ways in which people are targeted?

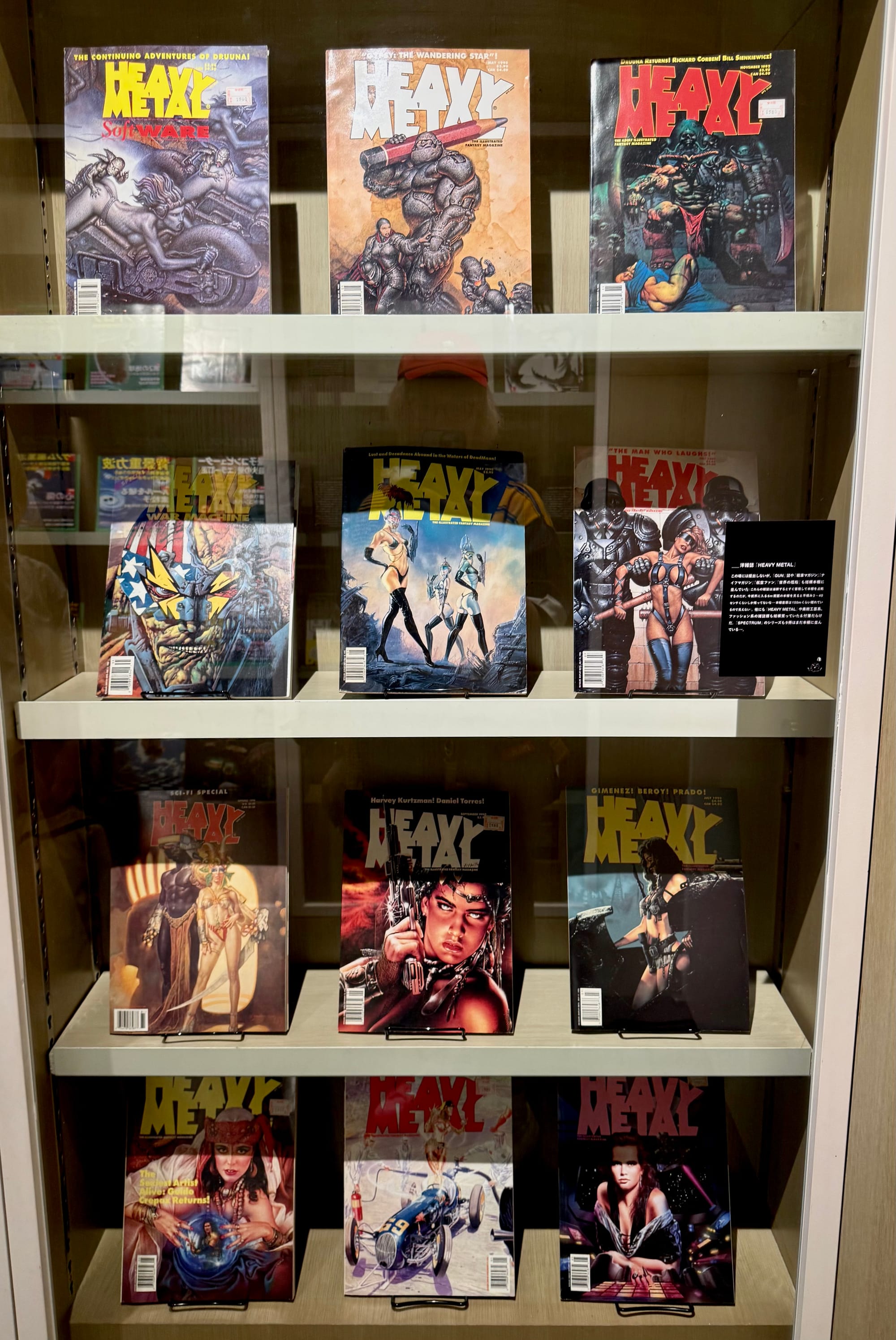

At a time when many subsequent generations of science fiction writers were taking inspiration from the works of their peers while attempting to advance the medium by imbuing these works with their own experiences, Shirow placed great interest not just in the works of international writers but the ways in which technology was fundamentally shaping a rapidly-modernizing domestic and global society. In one corner of the exhibit, walls were lined not with Shirow’s own artwork but the works that inspired his early career: issues of Heavy Metal magazine whose dark fantasy, science fiction and erotica elements often merged the boundaries of robot and human in its scantily-clad female characters and the augmentations that defined them.

On another wall were not issues of science fiction stories, but real-world science magazines that were not just reporting on research, but the philosophical implications of these advances on the society we live in. The technology was merely the start for depicting these worlds and the way people exist within them, which would become the basis for the cyberpunk-infused and militarized worlds he would eventually develop across his work.

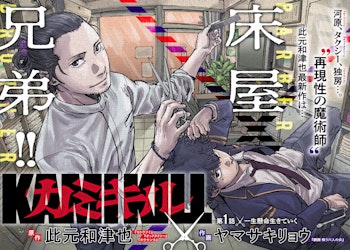

This exhibit was notable for being the first to bring his manga works like Black Magic, Orion, Appleseed, and Ghost in the Shell under the same exhibition roof, and it makes it the perfect place to witness just how much this idea of militant and human augmentation and the relationship between humans and technology in society permeate throughout his work.

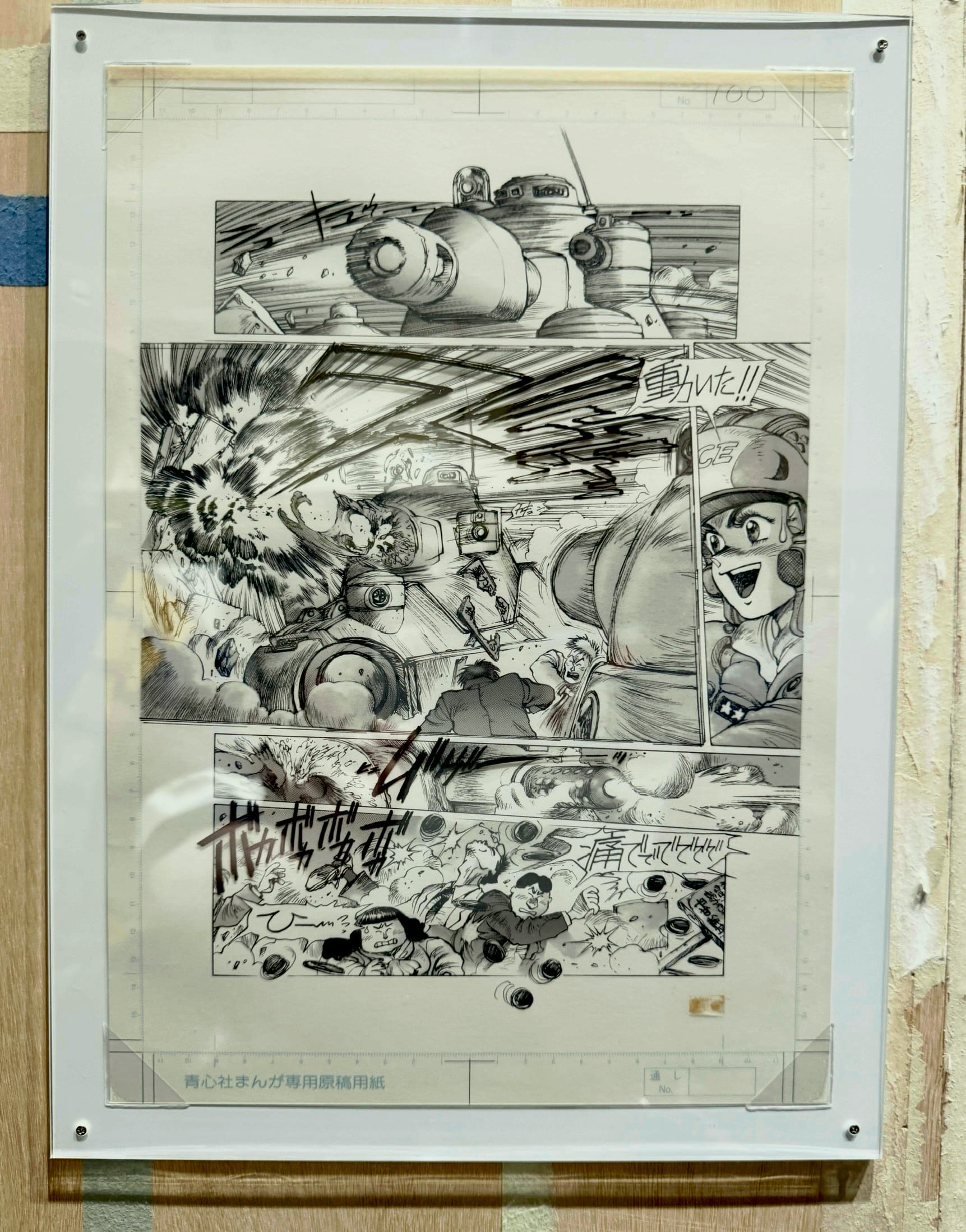

What helps to sell this to the reader isn’t just the story but just how he draws this world in each manuscript. Rather than his characters merely discussing these events, we see them manifest in the fully-realized and highly-detailed worlds hand-drawn in every panel. Whereas some artists may frame scenes in such a way that avoids needing to draw so many details of the world surrounding the characters, Shirow takes a voyeuristic pleasure in depicting these moments almost as much as he does in emphasizing the often-feminine bodies of his protagonists.

Worlds are vast, and by peering closer into each panel and manuscript on display its possible to pick out both the technology and the wear of everyday use that emphasizes the way this tech is both embedded and relied upon. In Black Magic, a doujin work created prior to his professional debut, the dense science fiction set in a civilization on Venus with both bioroids existing amongst society and cyborg warriors, an intense focus on world-building over the narrative can feel jarring, but it helps this vastly-disparate setting feel real and lived-in.

Through his art we see the worn-down technology of the world and we get glimpses of the military conflict between the remaining humans and these robot soldiers that depict a struggle for survival and a question of tech gone wrong. In doing so, attention is given to ensuring these machines, if not realistic to current advancements, are plausible, with an almost-mechanical, pieced together hunk-of-bolts-esque construction that bears the weight of the human hands who are now facing the consequences of their own creation. You see it in Dominion, also, with the worn-down walls of the military barracks and the vintage-future tanks wrapped in a comedic shell set on a polluted world with androids fighting a government organization’s attempts to alter the human genome rather than fixing the core problems.

Which all ties into Shirow’s work on his magnum opus, Ghost in the Shell. Particularly in Dominion, through its mix of androids and humans and technology as an integrated and natural part of everyday life, we see questions on how humans can and should be changed by the growing advancements in order to survive and persevere. Ghost in the Shell takes this further, with protagonist Major Motoko Kusanagi’s brain and humanity housed within a full-augmented cyborg body as a result of a childhood accident that gives her a new chance of life, but also leads her into a dangerous line of work. In the most famous Puppet Master investigation from the manga that became the root of its film adaptation, access to the online world and technology directly inside the brain makes her and those like her vulnerable to hacking and hijacking, even going as far as to allow the implanting of false memories.

How can you tell what’s truly human if you can be altered at the very core in such a way?

It should be no surprise that, even in an exhibition covering much of the director’s career (even if it conspicuously avoids showcasing much of his near-pornographic later work that lean into the military-techno erotica of Heavy Metal to an arguably greater extreme degree with often-underaged characters), Ghost in the Shell takes up much of the showcase. Even in an area featuring the work of other artists paying tribute to the creator, many draw fan works linked to Ghost in the Shell and espouse its influence on them.

You see it in the science fiction works of today. The question of humanity in a cyber society resonated, as did the world that series constructed. While the ideas of the series weren’t new and were merely an evolution of his career to that point, the success of the manga and particularly its subsequent anime shifted the industry around this question that creators have pondered seemingly-endlessly ever since. Especially in the growing age of connectivity that was starting to gain prominence in the 1990s during the serialization, questions that Shirow had already been pondering took on new meaning.

Much of what Ghost in the Shell embodies, and much of Shirow’s artistic style as a result, would come to shape the defining image of cyberpunk as a subgenre of science fiction. While the manga was not devoid of its comedy, its the more serious philosophical musings on the boundaries of human and machine that later anime adaptations emphasized that became a core aspect of science fiction in the years that followed, certainly aided by Ghost in the Shell’s mainstreaming in the Japanese zeitgeist coming around the time of Neon Genesis Evangelion. In a full circle moment, The Matrix, films heavily inspired by Ghost in the Shell, returned to these ideas with Japanese creatives with Animatrix, you had series like Serial Experiments Lain touch on the topics, and even more recent entries in long-time franchises predating Shirow’s manga debut like Mobile Suit Gundam have not been immune to considering this question.

Shirow throughout his career focused on the ways in which technology interacted with the world around us, embuing it into his intricately-detailed worlds and the characters and themes he tackled. The industry at home and abroad, in literary form and in film, have been altered by the existence of not just his stories and the culmination in Ghost in the Shell, but in the way he depicts his world that probe the audience into thinking deeper. Would Shirow’s stories on their own resonate, without his signature style embracing analogue mediums far beyond when many artists shifted to digital to depict dense scenes that remind us of the people living with this technology? After reading his detailed explanation of the exact tools used for every volume of Appleseed and beyond and seeing his tools displayed in a case, I don’t think so.

It’s Shirow’s method, just as much as the intricate art and philosophical stories, that have allowed him to have a transformative impact on Japanese science fiction. Wandering around this exhibit, it’s hard not to be overwhelmed seeing this work up close. To see the art of someone so influential up close is powerful to see. Maybe try and see the exhibition for yourself, while you still can.