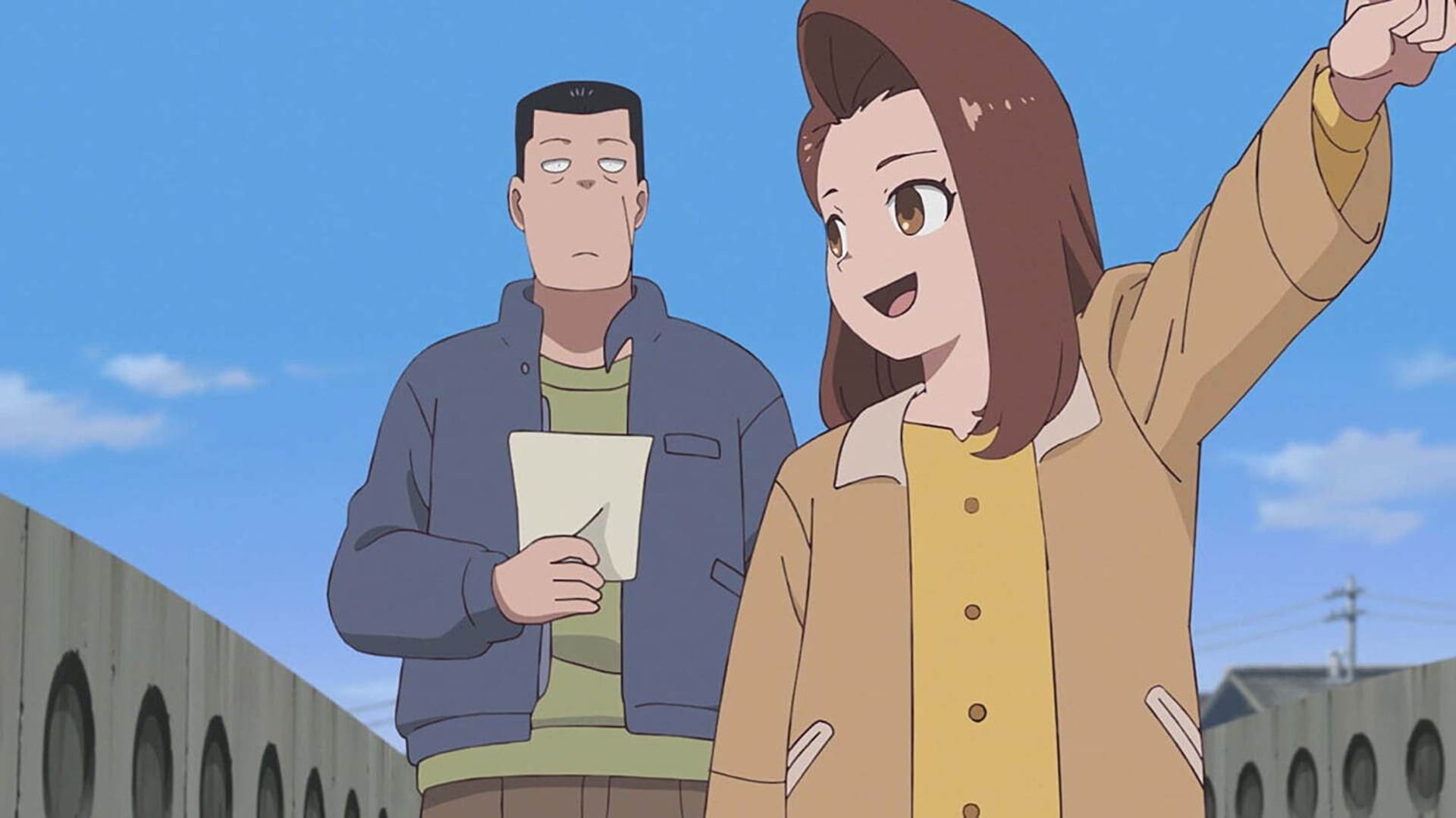

Minoru Akutsu (played by Kaoru Kobayashi in the past and Junki Tozuka in the present) is dying, trapped in his jail cell lying on the floor with pained breaths that suggest he is not much longer for this world. Beside him is a flower (Pierre Taki), goading him. But the flower is like an old friend, having seen his life since the 1980s to the modern day. With what is likely his final night on this earth, the two engage in a conversation about their life. The home they grew up in on the hill, and a woman named Nana and her son that he came to view as love and family. His life as a yakuza, growing in importance. And the events that caused that life to shift, his motivations for it, and what that may have done for the family now living separate and outside the walls he is stuck inside.

The rambling, dying thoughts of an old man in prison are not the normal subject of an animated movie. Then again, The Last Blossom’s heartfelt ode to going to the ends for a family through the eyes of a flower is not a normal film, elevating this idea through this unique framing device and the seedy yakuza world’s final flings with dominance in beautiful ways.

Premiering at Annecy before releasing recently in Japanese cinemas, and for all its characters are (mostly) far more human than director Baku Kinoshita’s debut work ODD TAXI, the mystery and underground lifestyle explored leave the film feeling like a narrower focus on similar thematic ideals. This is no coincidence with screenwriter Kazuya Konomoto also joining the project after working on that film, bringing a melancholic touch to the topic without ignoring the humorous side of a talking flower that acts like a counterbalance of truth.

After all, Akatsu’s life in jail, while the event that brought him here is one he believes in, is filled with regret. He found a modest living in this rural home on the hills off of the protection money the yakuza could demand in their heyday. He could even be around for the pair of people he took in but could never admit to being in love with, drinking in the home with his yakuza friends and spending far more time around than would have been possible as a salaryman or otherwise. For all the questionable acts he engages with, he’s happy.

The family life we are made witness too is sincere to the point of achingly real in ways we don’t see too often. Ben E. King’s “Stand By Me” serves as a musical motif and the movie’s closing theme throughout, a beautiful song that embodies the relationship of this unintended couple so well. The song’s endurance as a love song for half a century, globally, comes from how it is so achingly in love with its subject. I can’t bear a moment away, so stand by me, I would do anything for you, so stand by me.

They tap this out and bang the doors of their cosy home to create an acapella beat of this tune, because everything around them is their relationship. Their connection is unbreakable, and it’s the core of the film. The only voice of, if not dissent, disquiet, to the relationship comes from the flower.

It’s the contrast between the aching love and this song, and the cynical flower that serves like a doubting and jagged inner monologue made anthropomorphic, that makes this story hit home. After all, it’s an honesty this flower makes manifest, allowed by their unique appearance making the frankness of their comments more palatable when it would feel rude from a human. The flower can chide Akatsu when he admits he was never able to admit his love to the pair, even if they both felt the same. The result adds a painful tinge of regret to the flashbacks viewed in the afterglow of life, hoping he did enough.

Everything about this flower is a contradiction. The Last Blossom’s Japanese title refers to the flower by name, a housenka or garden balsam, known for its somewhat pleasing appearance but the explosive way it distributes its seeds. It’s an animated character in an otherwise-subdued film - though the younger man is more active in his yakuza days, as a dying man he barely moves - feeling more in place in a Disney film than a human drama like this. For a film so realistic, the flower makes little sense, but it's through this that we can touch on a truth that can never be spoken otherwise.

The life built must come to an end, but that is true for everything in this film. The timing of the past-to-present, a journey from the end of a bubble-era Japan of excess and the view of never-ending prosperity with the organized crime at their strength seen for this family, falling on hard times as Japan and the yakuza scatter and fall like the seeds of a balsam. The pain of this dying man is not in the dying or even that he lost his family, but that he has no way of knowing if they cared or if the help that he established for them before things changed was enough to save them as things hit hard times.

It’s aching, painful, melancholic, and rather beautiful, and there’s nothing like it. While there are the noted similarities to some stories of ODD TAXI, the result here is entirely unique and elevated by its lean runtime as a film and characters so human even when they’re not. It means that, once we enter greater yakuza stories, the intense drama and tension of this is tinged with the domesticity being shattered for the all-too-familiar pain that, like the setting itself, nothing lasts forever. It’s nostalgic even if you never lived it, and a gut-punch even when you thought you were safe.

By the end, as the final breath draws near and the family outside and person inside the walls consider what was and what is, the question remains whether all of this was worth it. I’d say it was, and that’s why it hurts so much. The Last Blossom is a story that leaves everything on the table in its quieter moments just as much as it does elsewhere, where a sassy plant is the star and agent of cathartic release. As the credits roll, the feelings inside explode, and it’s impossible to contain what it introduced any longer. Just like a firework, or perhaps, a balsam flower.

It was worth it, in the end. It truly was.