In Bullet Train Explosion, as the gravity of the danger befalling shinkansen Hayabusa 60 becomes apparent to those inside the JR control center, a request is made to unearth the reports and documents relating to an all-too-familiar. A hostage situation caused by a bomb unsuspectingly planted on a shinkansen train barallening towards Tokyo, a condition that the bomb will explode if the train dips below a certain speed. It’s all identical to the fate that befell Hikari 109 exactly 50 years prior, and that’s no coincidence.

Despite first billing itself as a remake of Toei’s 1975 film that turned the excitement and potential of the new mode of transportation into a social commentary and disaster thriller, it soon becomes clear that Shinji Higuchi’s Netflix Original project is actually a decades-late sequel to the beloved classic. Of course, much has changed in that time. What was once a single-route novelty has grown to a sprawling cross-country expanse of high-speed rail that’s the envy of the world, and the norm for millions upon millions of passengers every year.

It’s the lifeblood of the country, the beating heart of a nation that relies on it to function. The stakes, in theory, have never been higher if something were to go wrong. So why does this whole film feel so safe, devoid of danger and lacking any of the societal critique that gave the original film a sense of thrilling intensity and political bite?

There are two subtle but notable changes that completely shift the attention of this new film compared to the 1975 film. First, the film has an experienced SFX- and spectacle-driven director in Shinji Higuchi at the helm, who proved himself as someone capable of bringing intensity to boardrooms and bureaucracy in crisis against destructive forces. Junya Sato, the director of the original movie, was more in tune with yakuza and gangster character-driven action across his career, which explains why that film broadens the scope in an attempt to understand why someone would plant the bomb in the first place.

Secondly, whereas the fear of similar attacks on the new fleet was strong in the 1970s, this time JR are direct partners on the film, allowing the team access to real Shinkansen, direct access to control rooms and train depots, and anything needed to provide granular accuracy to train operation.

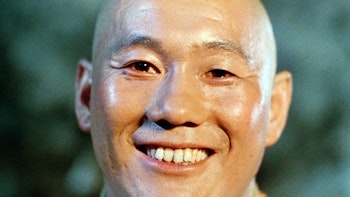

The result is a massive shift in perspective: rather than the thrill and emotion of the hunt, this is purely a fight for survival, driven by incessant competence from bureaucratic strategy to a conductor (Tsuyoshi Kusanagi) that will do anything to ensure every passenger arrives safely. An adoration to composure under pressure and the constitution of the railway.

Unfortunately, doing so sands the film of the identity and political tensions that gave the original film an identity. Bullet Train Explosion is a film where the terrorist themselves is a near non-entity, and the story is entirely disinterested in the why behind the pressing danger at its core. What made the 1975 film a fascinating relic of its time is the way the Shinkansen becomes the center of the universe and a mirror of Japanese society more broadly. One of relentless growth and prosperity, but not for everyone.

It was a window into dealing with a loss of power, a story of left-behinds desperate to be heard to the point they’ll blow it all up for a moment in the spotlight and a second chance. A full third of that film is simply spent existing alongside the terrorists, separate from the chaos unfolding on the tracks. It gave us a window into people driven not by blind hate, but a desire to find a future where they can be heard, even if just for a moment.

The 1975 film was too long, but at least it used that elongated runtime to make us care for the events on screen. This tale is similarly lengthy, but replaces that depth with a sense of ‘more’ the creative team forgot to define before the cameras started rolling. If anything, constant callbacks to the original, including playing archival footage from that film, just serves to highlight the comparative shallowness and shortcomings.

In the 1975 film, tension for the ticking clock of a train barreling towards Tokyo isn’t solely driven by its destructive potential, instead by the fact even the audience is conflicted between rooting for the heroes or villains. Even if no viewer would agree to blowing up a Shinkansen to prove a point. Aside from some voice-altered phone calls, the terrorist isn't even mentioned in this film until it's almost over, and their actual motivations to plant the bombs are outlandish. To even begin to parse their reasoning requires a strong memory of the 1975 film, and even then it’s incomprehensible.

At its most charitable, the motive lacks bite, or anything that could make us sympathetic to the cause. What was a challenge to a symbol of a new era has been reduced to a petty feud and melodrama silly enough to produce audible, repeated laughter as the truth is finally revealed. Worse, even if you were to care, there’s little danger they could succeed. By the halfway point almost every passenger is saved bar a few adorned to main ensemble status who are contrived a way to being stuck in the midst of a crisis.

The action is flashy and competently made, and there’s an almost-pornographic attention to detail. We see the control center led by Kasagi (Takumi Saito) trying to do whatever they can to cancel trains and adjust schedules to keep the rocketing explosives on track and bring the train and its passengers home safely, focused on the minutia of rail maintenance and technical detail. We see the driver (Non) carefully adjusting controls to make sure things work, and we get extensive insight into much of what is necessary to run a train network.

As a train fan converted to a love of the technical marvel of these machines during my time in Japan, it’s impressive. It just never feels like there’s any danger because of how well-oiled the JR machine is - it's almost like the fear of showing even a slight fictional flaw was a step too far - it’s nice to see the care these people have for the trains they manage. It’s detailed to the point the danger is diminished, which removes any suspense the train may be destroyed or disrupted.

This lack of tension is only compounded by character writing so shallow you simply don’t care whether the train or its passengers survive. Without getting to know the passengers and crew beyond an adoration for keeping the trains running or their single-sentence trope-ridden biographies, and without a motivated terrorist standing in contrast, they’re just bodies. Everything that happens is just stuff. Flashy stuff, occasionally well-shot stuff. But stuff. It just fades into noise after a time.

In 2025, the Shinkansen is a ruthlessly-optimized system, as much a part of the fabric of Japanese life as nature itself. And according to the film, nothing needs to change. The systems are perfect. That's why the terrorist has no meaningful motive, and why nothing that happens on screen really matters. Yet when there’s nothing to change, there’s nothing to challenge. There's no society or authority in need of reform, no matter how many empty platitudes you unleash. It's meaningless.

This is certainly louder than the original, but in making all that noise, they forgot to have something worth saying.