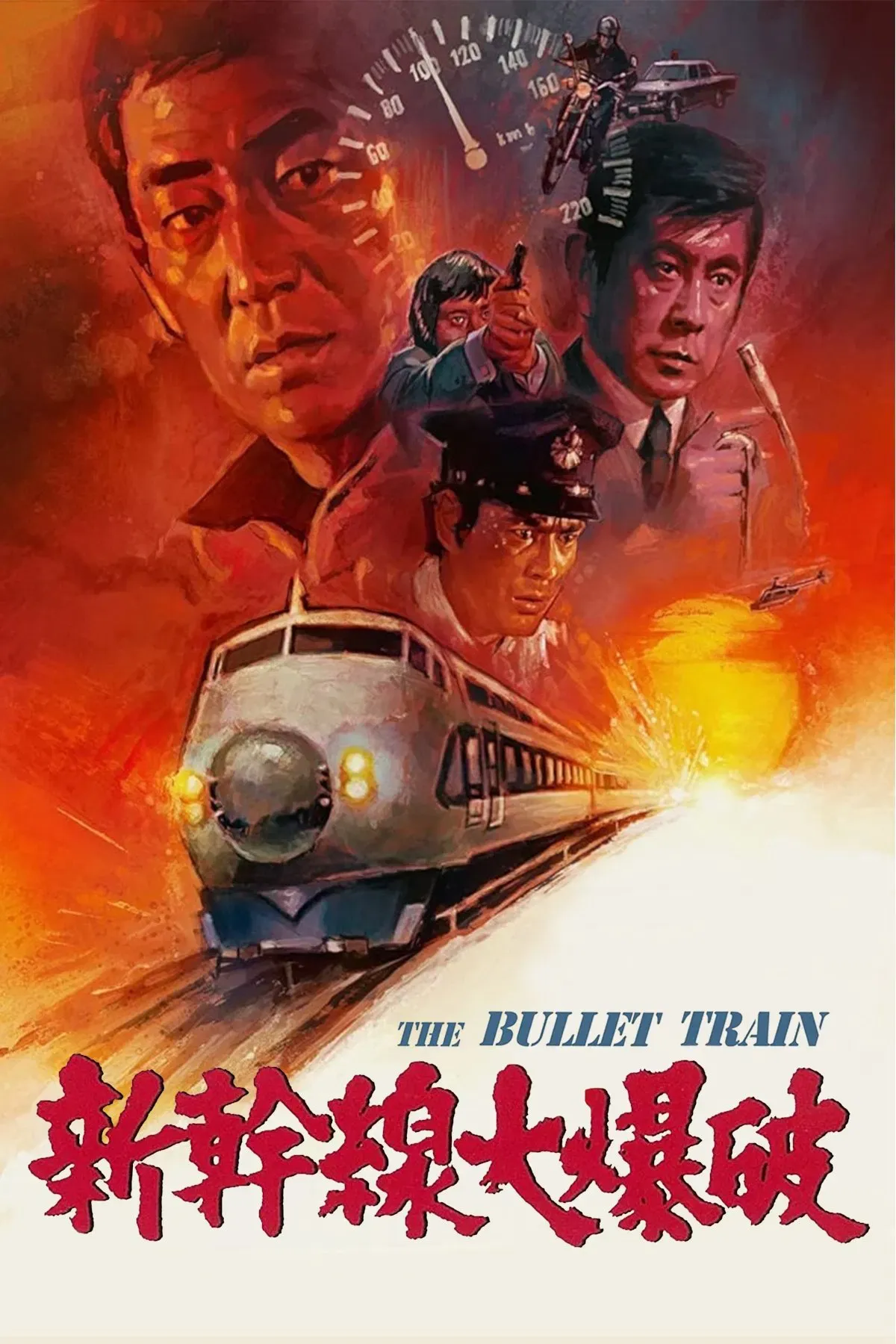

The 1975 Junya Sato-directed Bullet Train Explosion (released in English as The Bullet Train) is often misinterpreted in popular culture with a reputation that precedes it. “This is the film that inspired Speed,” many will chide before skipping right on by to watch Keanu Reeves attempt to stop a bus. It’s not an incorrect assertion, but it creates an impression the films are one-and-the-same bar their chosen mode of public transit and country of origin. Even this film’s name suggests a film with far more pyrotechnics than the methodical 150-minute tense slow-burn thriller you’re treated to.

To go one step further, this is a film that ogles the shinkansen it threatens to destroy as a thing of beauty, a new Japanese pride as much of a star in the film and a draw to the public as the actors in their prime. It was a new era, and this is a film which matches that opulence with excess, while remembering those who perhaps weren’t brought along for the economic ride.

After witnessing the bomb being placed, the film starts as Japan Rail receive an unusual phone call from an unknown assailant (Ken Takakura) informing them of the impending tragedy set to befall the Hikari 109 shinkansen. The bomb planted on the vehicle is programmed so that, if the train slows below 80km/h, it will automatically explode, derailing the vehicle and almost certainly killing anyone on board. The only way to stop the bomb is to pay the ransom, leading to a race between finding the assailants and saving the passengers trapped on a speeding bomb.

While not to suggest that Bullet Train Explosion is devoid of disaster-fueled spectacle, the film is far more level-headed in the face of such life-and-death stakes. With less time spent inside the train itself than would be expected for a film quite literally named after one, the result of such a creative decision is one more interested in our response to such a crisis from all levels from the command center and police, as well as the driver of the train (Sonny Chiba). It creates a far more character-driven film more interested in how people react to such a scenario and the reasons someone might have for perpetuating this terrorist act than the act itself. Yet the stakes and ever-present danger are just as imposing thanks to attempts made to understand the people behind the attack as well as those trapped in the middle of this crisis.

Take Tetsuo Okita, the assailant mentioned earlier. With a need to pay back debt the crime is borne from necessity, the money to be shared with his similarly-struggling accomplice. There are two ways to view Japan’s post-war era of unprecedented continuous growth and prosperity. It was an era of innovation and transformation that saw Japan rebuilt from the ashes of war with a modern sheen, the country growing to become one of the wealthiest in the world while innovating in technology like had never been seen. Areas like Akihabara became hubs of technical transformation, and Japan became known as a manufacturer for cameras, TVs and modern conveniences that transformed our relationship with the world around us. It made people rich like never before.

The bullet train was the shining jewel and symbol of this renaissance, the fastest in the world at the time of its creation connecting Tokyo, Nagoya and Osaka. Not only was it instantly popular, it became a symbol of national pride that connected people like never before, making Japan one of the first to build such high speed rail. But it was a pricy investment, and while it was no doubt a success, its price ensured not everyone could use it. And for all Japan prospered during this era, the money coming into the country didn’t reach everyone.

Bullet Train Explosion’s fascinating appeal is balancing set-pieces with complex characters that themselves paint a subtle critique on the imbalances and direction of the country. Tetsuo is a sympathetic down-on-his-luck man, and though his circumstances don’t justify planting a bomb on the shinkansen, time spent with him discussing his plans for a new life with the money and the pain inflicted upon him reflect someone who certainly doesn’t feel the prosperity of a country that proclaims all is great for everyone after decades of strife. He plans to leave and start a new life, and there are times where you can’t help but hope he succeeds.

Stand-offs with the police become more tense even when minimal in action because more than many similar films you don’t just care for the stakes of the heroes, but the antagonists. It’s not a case of wanting them to succeed, but sympathizing with how they reached the situation they’re in. And this isn’t to say the film is devoid of set pieces, taking advantages of the practical tokusatsu effects magic of Toei during this era to make great use of miniatures for shots of the shinkansen interspersed with stock footage and for some great set pieces, particularly one on the river during a tense money exchange.

Even minor characters have stakes, and become meaningful because you see their natural reaction to being stripped of control and left to fate. A young woman heavily pregnant and trapped on the train goes into labor under the stress, a storyline with deeper views on the overlooked bystander than many of its genre contemporaries. There’s more comedic moments that still humanize these characters, such as watching a more gruff businessman not bat an eye when the stranger next to them steals his cigarette and lighter upon hearing about the bomb placed on the train they’re currently trapped on.

It all comes together for a film far more compelling for the stuff that happens beyond the confines of the shinkansen and for the characters than any of the spectacle you may expect going in. It showcases ruthless competence for those running the train, particularly the level-headed driver, while humanizing those left behind in the marvel that allowed the train into existence at a time questions on the future of a divided Japan were being answered. It turns the shinkansen into a vehicle representative of Japan itself at the time: vulnerable, but powerful, capable, and a symbol of pride that people want to protect.

This is the context often forgotten with Bullet Train Explosion. The shinkansen is a cool piece, but it was a novel concept upon the film’s release at barely a decade old and envious enough to elicit pride. That’s why it becomes a target, so it can become a microcosm of the country in its story, and even if that story is a tad too long it remains interesting for this facet alone. As the film is set to receive an all-new remake courtesy of SFX master Shinji Higuchi at Netflix, its director and team are more than capable of replicating the spectacle and sheen of its titular vehicle. But can it capture the humanity a modern lens often forgets?