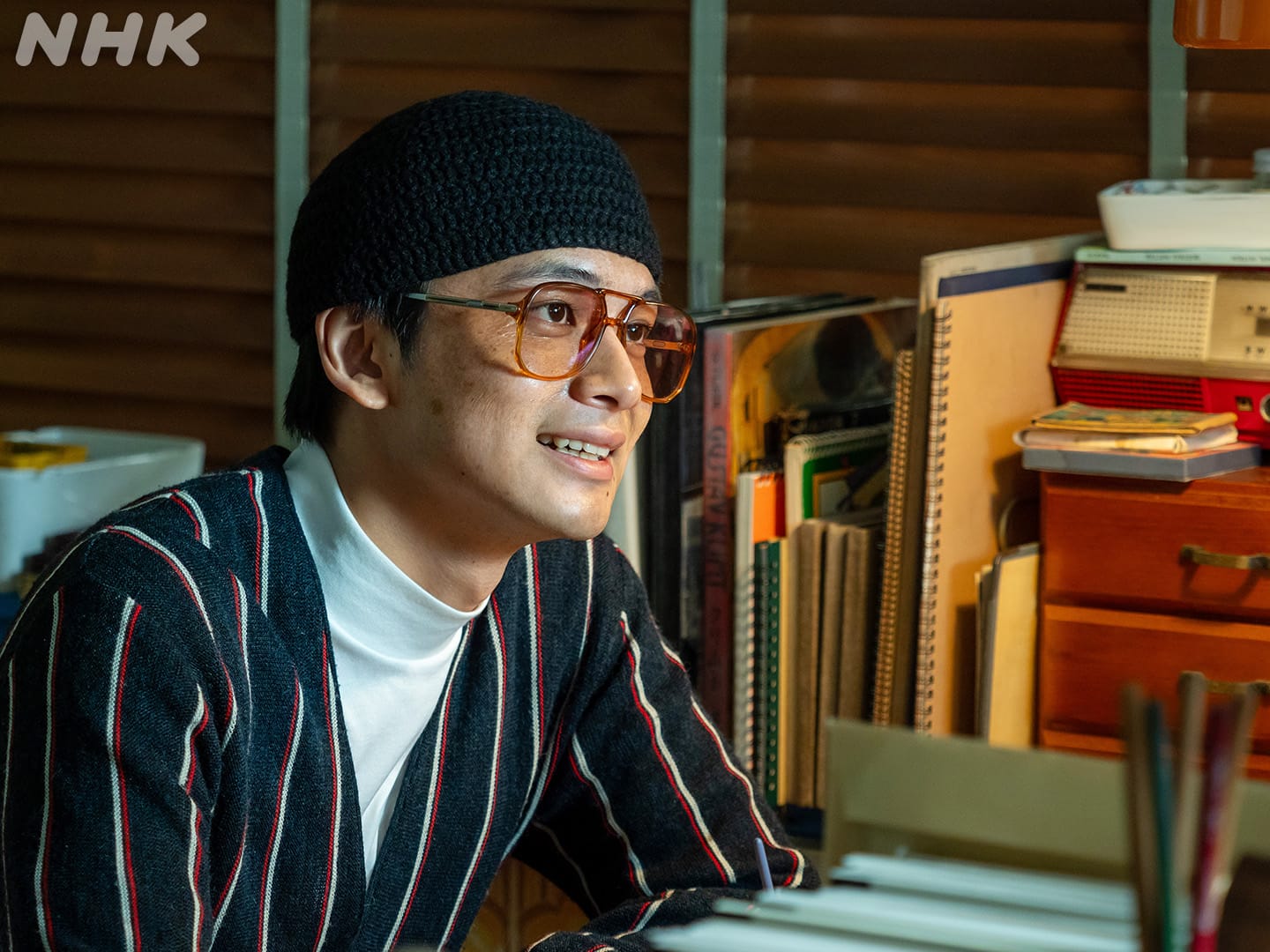

Almost every Japanese child has been raised on the lessons of the country’s ‘weakest and least-cool hero’, Anpanman. The boy made of red bean bread is far from the coolest hero, and he’s not particularly cute, but the character is an institution when it comes to children’s franchises in Japan. In much of his most beloved attributes, the character matches its creator, Takashi Yanase, a man whose coming-of-age during Japanese wartime and difficult younger years are the focus of an all-new drama, Anpan.

NHK’s long-running tradition of serial asadora (morning dramas) have consistently been some of the biggest dramas on Japanese TV for over 50 years. Broadcast five days a week for half a year in rotation every weekday morning, their prime morning slot on the national broadcaster makes them a major draw to audiences of all ages. Often they’re period pieces or biopics, exploring universal aspects or people in Japanese society or a significant cultural artifact. They’ll typically be coupled with an uplifting message of personal growth or overcoming hardship, and can even cover the lives of influential modern figures like the translator who first brought Anne of Green Gables to Japan, Hanako Muraoka.

Under such a remit, Anpan is the perfect show for this prestigious broadcasting block. Not only is the character more recognizable than any other in Japan, reports show almost 50% of all kids under the age of two have some sort of Anpanman-related merchandise, whether that be Takashi’s own Anpanman picture books or everything from toys to clothes to so much more that bear the character’s face.

Unlike other asadora based on real figures that are more true to the real lives of those the story is based upon, this is merely modeled after the real-life creator with liberties taken. Nobu Komatsu, the wife of Takashi and the promoted focus of the story, is known in the series as Nobu Asada. Still, Anpanman and its inspirations remain mostly true-to-life, making it fitting for those who grew up on the character or are about to raise kids of their own to witness this origin story.

In telling the story of how Anpanman came to be, it takes advantage of its daily serialization to detail how the pain of loss and bearing witness to tragedy led to the creation of this iconic character. At just six years old, Takashi is forced to move to Kochi Prefecture from Tokyo with his mother and brother following his father’s sudden passing, the Westernized mannerisms from his Tokyo life making him stick out in his new rural home. It was only others who similarly didn’t fit in that helped him adjust to this new home, whether that be the affectionate traveling bread salesman Uncle Yam who bears passing resemblance to Jam Ojisan in the series, or Nobu herself.

As the weeks go by we see the creeping rise of Japan’s off-screen militarism begin to creep even into rural life in this far-flung town, with nationalist flagwaving and glorification of war becoming ever-present even as many lost access to essential food and supplies. Takashi’s family sees their abundance chipped away, and the experiences of military life for both Takashi in the army and Nobu on the home front turn both characters away from the pressure of conformity to Japanese military celebration towards the morals of justice that Anpanman embodies.

It even makes strong use of the daily broadcast schedule to drip-feed its story with the feeling for the passage of time, rather than feeling like a longer story chopped up into smaller segments. That being said, this is still far from perfect. The shorter daily runtime means scenes that take place immediately after another on two separate days require immediate flashbacks to keep audiences informed. The show is also forced to simplify the solutions it has for any conflict to keep runtimes under 15 minutes, not helped by an extended opening title sequence.

Not that keeping things simple is necessarily a bad thing considering the show’s intended audience. These are early-morning or daytime shows, with an expectation that families may watch them before work or school, or at least catch up together through omnibus weekend broadcasts or on demand. Coupled with the fact these remain some of the drama with the highest broadcast audiences, they’re designed by NHK to be accessible to all, and digestible for younger audiences who may not be able to approach the more mature content of adult evening dramas.

It might seem unnecessary to an older audience why we need a narrator to explain the joy on a child’s face or the shock of realizing it may be mean to bully the kid that just lost their father, but it ensures that younger audiences can follow along with Anpan even if their parents aren’t sitting alongside them, without entirely removing more difficult or darker topics from the conversation.

It places Anpan, and all asadora, in a unique position. These are tales embodying Japan’s moral character, making any asadora a fascinating window into the society from which it was produced. The choice to promote Anpan with Takashi’s wife as the protagonist with far more time spent exploring the years prior to Anpanman’s creation as Nobu forges her own career that inspires and drives Takashi’s future trajectory, we see the show represent a growing desire to bridge gendered stereotypes that’s also been a concurrent theme in other recent asadora.

Although events as we approach the halfway point remain in wartime Japan, a key purpose of making Nobu the protagonist is to explore her role as one of the first female post-war journalists in Japan. A growing interest in the question of journalistic integrity amidst corruption scandals in government and the recent Fuji TV scandals makes the choice to center her character also indicative of growing Japanese interest in the role the media, especially as the topic gets similar attention in other ongoing drama like News Anchor. In an increasingly conflict-driven world where the question of Japan’s involvement is a near-constant topic of domestic discussion, the extended focus on Takashi’s military service is also noteworthy.

At its core, this series takes a compelling character and the people who brought it to life, and uses it as a reflection of modern society. What lessons for the present can we learn from the past, and how can that be condensed into bitesized chunks for the broadest possible audience? In this, Anpan embraces what NHK’s asadora have historically done best, and this is what makes the series a compelling watch.

I did not grow up as a kid in Japan, so I wasn’t one of the millions of kids who grew up loving this weird but beloved hero. Yet I still see Anpanman’s hope everywhere. There’s a museum dedicated to the character in Yokohama, and if you walk by, joyful screams of children fill the air. In Anpanman's existence, there is hope. More than just a silly hero with a bread-based ensemble, the character will save his friends and at times literally feed parts of his anpan self to those who are hungry or less fortunate.

'A justice that never overturns'. The daily broadcast schedule of this series allows us a slow but entertaining window into the journey that brought the character to life, made accessible for anyone to understand. And it succeeds at that. Thanks to the series, I understand now why Anpanman is so beloved, and see the positivity the series embodies.

The asadora is unique in Japan because its popularity and existence on a national broadcaster allow it a unique space in the Japanese media landscape no other show can provide. They're often worth checking out for this fact alone. It just so happens that Anpan is also one of the better shows to take advantage of the format in recent years.