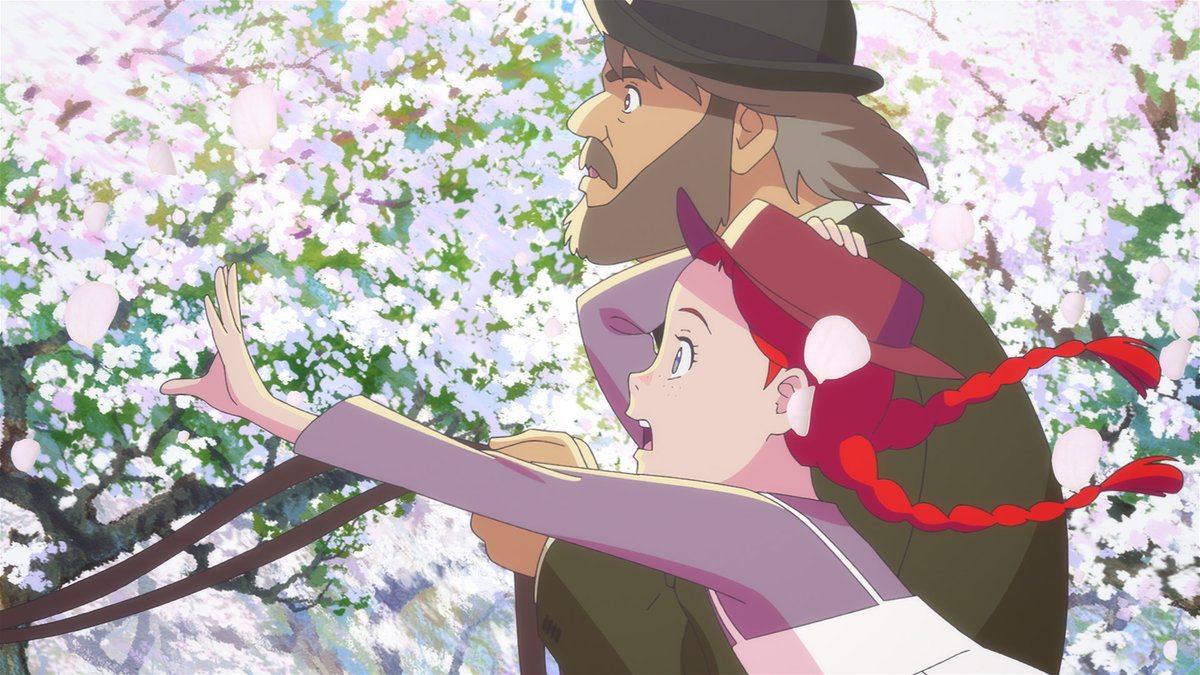

The recently premiered Anne Shirley anime series is just the third anime adaptation of Lucy Maud Montgomery’s cherished Anne of Green Gables novel series. It continues a long legacy of hope in Japan that has carried on since World War II.

As a Canadian, I recognize the cultural significance of Montgomery’s Anne of Green Gables novel and its impact on Canadian literature and pop culture. However, I didn’t finish reading the first book when I was younger because it wasn’t really my type of story. When I first learned how popular the series was in Japan during my English undergrad, I was definitely surprised.

Why does Japan love the fierce, red-headed Anne Shirley? And why has her story stood the test of time? Let’s take a closer look at Anne’s impact on Japan.

The Missionary & The Translator: Anne’s Journey to Japan

Anne’s journey to Japan begins with the meeting of two women: Christian missionary Loretta Leonard Shaw and Japanese translator Hanako Muraoka, who provided the first Japanese translation of Montgomery’s novel.

Shaw was a Canadian working in Japan on behalf of The Missionary Society of the Church of England. She became the Head of the Department for Women and Children’s Literature at the Christian Literature Society of Japan in 1932 when women’s education was growing in both countries.

Muraoka, meanwhile, was born and raised in a Japanese family of tea merchants, who were devout Methodists. When she was ten, she left home to attend the Toyo Eiwa Jogakuin school, founded by the Methodist Church of Canada. Here, she underwent an intensive English-based education, mixed in with her regular Japanese studies in the morning. Soon after graduating in 1913, she began translating and publishing various children’s short stories, later releasing her first book, Rohen, in 1917.

In 1930, Shaw and Muraoka met at the Christian Literature Society of Japan, where they regularly engaged with spiritual reading material. They soon collaborated as editors on the magazine, Children of Light, while Muraoka was working as a radio host and raising a family of her own. Their friendship wouldn't last, however, as Shaw was in poor health and under pressure to return to Canada due to Japan’s escalating World War II tensions in 1939. Before parting ways, Shaw gifted Muraoka a copy of Anne of Green Gables in hopes that she would be able to translate it into the Japanese language. Shaw returned home to New Brunswick and died a year later from cancer.

After the bombing of Pearl Harbor in 1941, Muraoka quit her radio host job as Japan entered WWII. During this time, she began reading Anne of Green Gables and secretly translating the book into Japanese in 1943. She finished her translations during the war and would hold on to it after it concluded. It wasn’t until 1952 when the publisher Mikasa Shobo released Muraoka’s Japanese translated book under the title Akage no An.

Although she planned to visit Prince Edward Island, the setting of Montgomery’s original novel, Muraoka sadly passed away in 1968. However, her literary legacy lives on through her first translation of Montgomery’s work, setting the standard for newer translations in the future. Several new book editions, with updated translations, stylized covers, and illustrations have since been released.

Redhead, Revolutionary, Romantic

According to the BBC’s Robin Levinson-King, Anne of Green Gables was one of the few English language books to be translated into Japanese. Since it was foreign and cheap, it was easy to provide to libraries run by the U.S government during their occupation of the country. As such, it became an essential novel to teach in Japanese schools during the 1970s because it opened up conversations that weren’t normally discussed in Japanese society.

One of these issues is gender and the broader expansion of women's roles in society. King cites a Japanese literature teacher from the University of Tsukuba, who explained that the novel was about “an orphan girl who proves her heart and mind is just as good as any boy's,” which resonated with Japanese women who wanted to be free of traditional gender roles.

Three Magazine’s Sarah Laing supports this notion, writing that Japanese women appreciated Anne Shirley’s independence, freedom, and determination. She suggests her universal appeal stems from her endless imagination and optimism after enduring a harsh childhood in the orphanage. As an outsider in a new community, she works hard for acceptance from her foster parents and friends. Ultimately, Anne wanted to find her place in the world, which Laing writes is something people from all backgrounds can relate to.

However, Anne is also viewed as a cute or “kawaii” character to many Japanese because her story is filled with beautiful scenery, pretty clothing, and cheery tea parties. It is a pastoral story that shares many similarities with Japanese slice of life and “iyashikei,” or healing titles, working as a form of escapist fiction for readers wanting to find a good distraction.

These dual qualities demonstrate why the character is a Canadian icon in Japan and how Montgomery’s story endures in the country.

Anne Shirley’s Legacy

The legacy of Anne of Green Gables novel remains prevalent in Japan. It was previously adapted into a popular 50-episode TV anime series for Nippon Animation’s World Masterpiece theater series, with the show still receiving the odd rerun. Studio Ghibli’s Isao Takahata was the director, while a young Hayao Miyazaki worked on scene designs and layouts for the first 15 episodes.

Many Japanese tourists have also travelled to Cavendish, PEI in Canada, of which the novel’s Avonlea setting is based on, and where the Green Gables house sits as a heritage place. There was also an Anne of Green Gables replica house built at the Canadian World theme park in Ashibetsu, located in Japan’s Hokkaido region, which has since been abandoned.

As we welcome the new Anne Shirley anime series this April, let’s remember Muraoka’s efforts in translating the book into Japanese and kickstarting a country’s strong connection to a Canadian redhead from a small island.

Works Cited

Akamatsu, Yoshiko. “Anne in Twenty-first Century Japan.” The Anne of Green Gables Manuscript, https://annemanuscript.ca/stories/anne-in-japan.

King, Robin Levinson. “Anne of Green Gables: The most popular redhead in Japan.” BBC, 8 May. 2017, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-39809999.

Krzewinski, Agatha. “How Anne Became Popular in Japan.” Anne of Green Gables, anneofgreengables.com/blog-posts/how-anne-became-popular-in-japan.

Laing, Sarah. “Why Anne of Green Gables Is Huge in Japan.” Three Magazine, 29 Nov. 2024, threemagazine.com/culture/why-anne-of-green-gables-is-huge-in-japan.