In 1964, a doctor was arrested for breaking the Eugenics Law. Not in the way it was typically applied, but there was a method to this. The doctor, Masao Akagi, was one who specialized in gender reassignment surgery for trans women, removing their masculine sex organs and reconstructing them as a vagina. Some of these women, excluded from society, relied on sex work to survive, but couldn’t be prosecuted under prostitution laws due to male documentation despite the desires of those above. So, they found their scapegoat. A reconstructed body is infertile, right? The case, known today as the blue boy trial, halted such surgeries in the country for the following three decades.

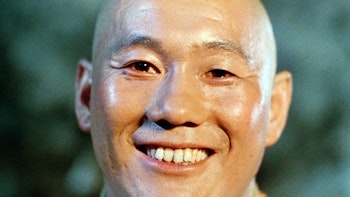

The Blue Boy Trial movie of the same name is exploring this period of Japanese history in a somewhat-revolutionary manner. While we’ve had stories featuring the stories of trans characters (2020’s flawed-but-still-popular Midnight Swan), and movies featuring trans actors, these facts rarely overlap. Indeed, what makes Blue Boy Trial so unique even before discussing the quality of the film itself is the array of openly-queer and trans talent both behind and in front of the camera, unheard of in major studio films even beyond Japan. Director Kashuo Iizuka is an openly-trans man, while the trans characters are similarly portrayed by trans women. Lead actress Miyu Nakagawa makes their acting debut eight years since their transition was the center of the 2017 documentary Onna ni Naru.

This true story places the trial and its impact on queer history in Japan against the backdrop of a changing country and the pressures it had in rebuilding its image and stamping down on unsightly acts. In many ways, Japan then mirrors the Japan of today - a country facing a renewed global focus against the backdrop of an Olympics and a World Expo, seeking to shape its image and project a new nation to the world. In the 1960s, it wanted to remove the unsightly visibility of sex work and things that seemed to make the country appear less developed, but they had a problem when it came to the “blue boys.” Without the terminology we would use to refer to trans identity today, these were trans women, many of whom were involved in sex work as mainstream society rejected their existence.

The government had an issue with them, since their legal status as men on family registers and official documentation made them immune to prosecution under typical laws regulating the practice. So police went to the source and arrested the doctor conducting these surgeries under the pretense of narcotics and eugenics laws, the hope being to banish them from this last vestige and portray Japan as a country immune to such “deviancy,” as they would refer to it. Sought out by Akagi (Takashi Yamanaka) for representation, lawyer Taku Kano (Ryo Nishikada) takes on the case, going to the women who had surgery under his care to bear witness.

Each lives very different lives. Mei (singer-songwriter Ataru Nakamura) is jaded by authority and hides behind the revelry of sex work. A-ko (Izumi Sexy) is trying to open her own bar. But it’s Sachi (played by the aforementioned Miyu Nakagawa) who could be the key to the case. Unlike the other women, she’s not in the world of sex work. She lives a somewhat normal life, working in a small cafe and happily living with Atsuhiko (Ko Maehara), a salaryman in Tokyo. Breaking the derogatory stereotype many have formed, she could be key to helping a society that doesn’t understand these women why they matter and deserve a space in this world to be themselves.

The film plays in the context of the trial, beginning almost immediately with the initial arrests and eventual scapegoating of the doctor and continuing through to the trial’s conclusion. Yet to portray this as some mere courtroom legal drama would not only misrepresent a film that spends surprisingly little time in the courtroom except when it matters most, it would mask what makes this truly essential viewing.

Blue Boy Trial is a story less about a single legal case but the trans experience in Japan both then and now, centered not on the doctors, nor the medicalization or exploitation of trans lives, that similar works seek to center. This is a film about these women trying to find a place to belong and finding a society hostile to seeing them as human in the process, and the desire to build a community and home despite these challenges.

Each character plays a role in this. A-ko’s character, fittingly for the “mama” of her upcoming bar, is the mother of this misfit band of trans and queer people seeking a place to be themselves, and will do anything to protect them. Izumi Sexy herself is the owner of a queer bar in Shinjuku’s Ni-chome gay bar area with this being her first acting role, but she dominates every scene she’s in as a veteran in what feels almost-documentarian in her character's desire to protect the people around her.

The bar is a chance more for her and the people around her to realize their dreams. she can perform on stage, and begs for Sachi to return just to create dresses as a seamstress and designer like she always wanted when the two first found each other in the gay district and discovered their true selves together. As the group prepare for the opening, their sanctuary and chance to be free from the prying public is on the roof or inside this space, and true happiness explodes from this. Which is why she goes to the trial and faces that fury, in the hope that it will help others.

Sachi’s forced to choose between the solitary of her current life with the possibility that returning to that open visibility of her identity could harm her relationship and everything she’s built, and maintaining silence with the likelihood no one can find the happiness she now enjoys. The relentless press, and an establishment who see natalist productivity, retained war spirit and national identity above humanity brings a true question at the heart of the trailer, these characters, and every aspect of this movie: are you happy?

The fact Masao Akagi’s role as a doctor or this side of the trial is barely featured is not an issue, it’s the film’s greatest strength. Because he’s not the important person in this trial. This was a trial initiated because of the existence of trans women, relied on their testimony, and determined the legality of gender reassignment surgery for all genders for decades to come. Even with the surgery now legal, the impact of the ruling is still felt in the queer community, and in how they’re discussed and perceived. The least that can be done is placing them in the forefront in a way other stories have fallen woefully short is what the film does best.

And this isn’t just placing queer people at the forefront and calling that enough. The film is shot in a manner that emphasizes this framing and gives them the space for their story to breathe. Despite their lack of prior experience Nakagawa and Izumi Sexy convey some of the strongest acting performances of the year within Blue Boy Trial, with monologues and moments that would induce tears from even the coldest of audiences.

This is an important film, but it also happens to be one of the year’s best. At a time when the lives of trans people are becoming a focus around the world, seeing a work where these stories are told from the people living them matters. It’s a story that begs a cisgender audience to listen without leaving queer people behind or twisting lives to a tragedy for sympathetic eyes, creating a more complex, nuanced and wonderful retelling of these events that captures just how far we’ve come, and how much further there is still to go.