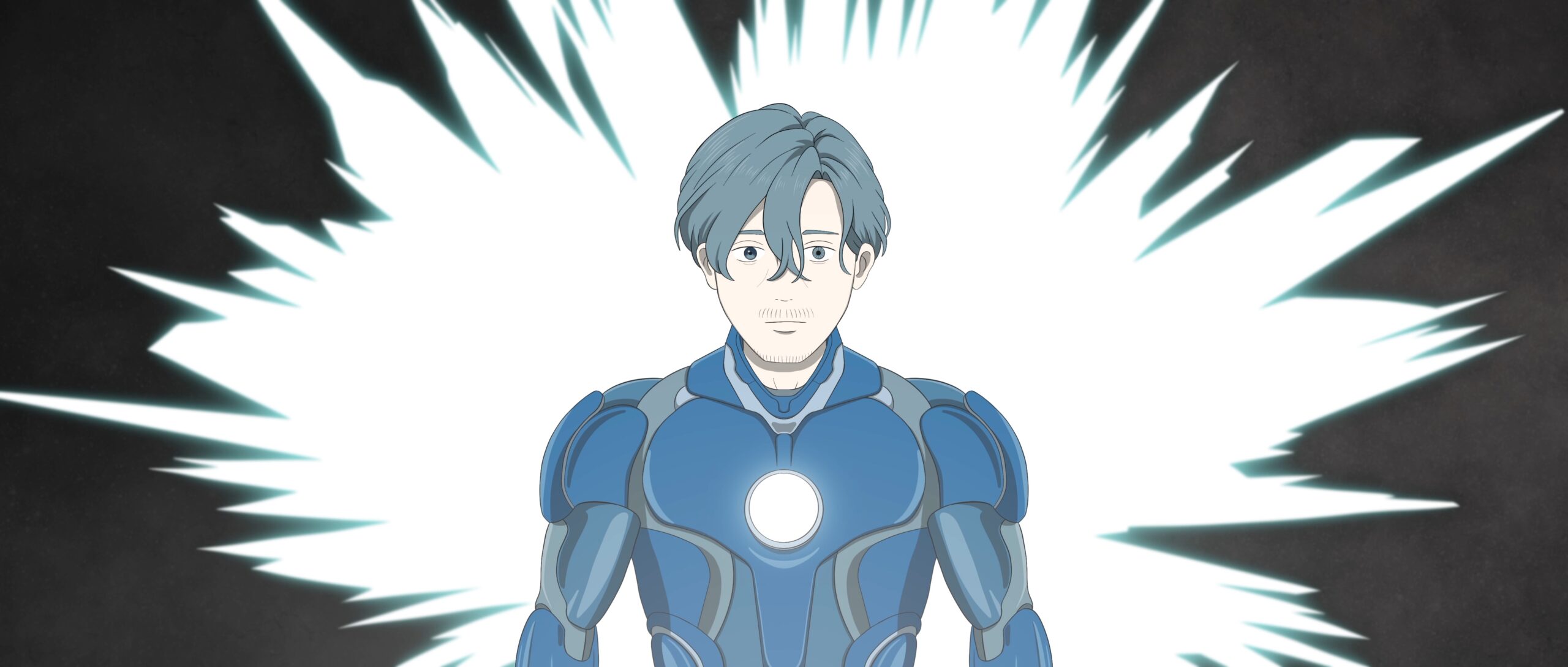

Creating even the most mediocre film is no easy accomplishment, never mind taking on the challenge of masterminding script, direction and animation solo on your debut feature while wrapping production in just 18 months. To say that what Ryuya Suzuki has accomplished with Jinsei is impressive would be an understatement. It just also happens to be one of the best animated movies of 2025 so far, with a fist firmly raised against the rot society would rather avoid confronting.

Our protagonist (voiced by rapper ACE-COOL) has no name, but he has many monickers. Se-chan, Kuro, Zen. God. As a child he was introverted, not helped when his mother is killed by an elderly driver, leaving just him and his father-in-law living alone in rural Japan. He’s bullied, referred to as a shinigami, only making a single friend who convinces him to join in his dream of becoming a male idol. This shared goal and the aspirational image of the male idol is one of the only things he can latch onto, with the proceeding story following this journey and beyond over the course of a century.

Jinsei exists thanks to a crowdfunding campaign of 359 strangers in 2022, and the circumstances surrounding its production and the recency of COVID-19 shutdowns are certainly an influence on the final film. Suzuki has admitted that, rather than meticulously planning the story of this movie in advance, he merely followed this character’s life wherever it took him, an approach that risks overwhelming the audience with its sudden shifts in subject and tone but just about keeps a throughline pointed at exposing flaws in Japanese society.

It’s a method most apparent in the evolving stream of topics the film tackles over the course of 90 minutes, never sticking with one idea despite the fact each could easily serve as the subject matter for an entire film in itself. The first third is a perfect example of this. As our protagonist and his friend, a blond-haired transfer student named Kin (Taketo Tanaka), seek fame as idols, they find the journey comes at a cost; working with a famed pop mogul almost certainly modeled as a slimy stand-in for Johnny Kitagawa.

These young boys were promised fame and fortune, and to that they get their wish. Our mogul’s tentacle-like connections across the industry give them opportunities others could only dream of. If they played along. The unspoken secret of the real-life Kitagawa’s sexual favors against his young, often underage talent, was only finally reckoned with following his death when the BBC released a documentary publicly exposing how the magnate would rape and exploit his talent before rewarding them with starring roles, a Faustian bargain that the film pulls no punches in replicating.

While news programming eventually forced a nationwide reckoning with the ways the Johnnys media empire silently allowed this abuse to occur, the broader entertainment industry has often shirked away from exploring the deeper issues that allowed this open secret to go unpunished for so long. It’s hard not to see how the broader # MeToo-style reckoning with the debate surrounding the Oscar-nominated documentary Black Box Diaries or the ongoing fallout to the Fuji TV scandal as the residual exposing of abuse for how the industry fueled or turned a blind eye to these acts.

The fact Japanese film or TV have rarely even passed mention to the topic makes Jinsei's direct portrayal of the abuse (and our passivity to it) as intriguing as it is damning. Jinsei is unflinching, providing guilt by association to its audience for simply watching rather than stepping in to make a difference. It’s formidable, brave filmmaking, yet this is just one part of a film with so much more to say.

It helps that our protagonist, while not a passive or unimportant figure, is a blank slate stripped of even his name. It allows his character to morph and evolve more easily as we shift from this 2010s origin to the present day and beyond in response to new subject matters. In the present day we’re thrust into the griminess of Kabukicho and into the lives of the homeless and the Toyoko Kids that roam the city. These runaways are the people falling through the cracks of Japan’s social safety net, people whose circumstances and mental health issues see them fall into the found family communities that sprout from these seedy streets.

Rather than helping them, we witness active attempts to push them out of sight and mind. Once Kabukicho Tower opened, a glitzy new building erected in the heart of this town, the open square at its base was cordoned off as an ‘event space’ that saw those with nowhere else to go pushed away by a new army of security personnel. Rather than helping these people find new lives off the streets (circumstances that often leave these people prone to exploitation in underage sex work and more), the hope is they can be ignored as long as lucrative tourists don’t have to look at them.

Our protagonist, in the shadow of his idol days, becomes a vessel that attracts the similarly-wounded to exist in the pain, the grime of their pasts bringing community. With age our protagonist has evolved into an almost-new character from who we knew, yet the nameless life he lives allows him to become whatever those around him project onto him. From friend, child idol and victim, he now becomes a symbol of warmth, something to latch onto in darkness.

As the film proceeds through the century-long ten chapter structure that encapsulates this character’s life, no area of Japanese society is spared from criticism. The forgotten youth and homelessness, drugs, power, money, even the political establishment itself and the self-embellishment by those in power. this topic in particular has come to sharp focus as a result of scandals facing the ruling LDP, and was even a factor in the party losing its majority at the 2024 elections.

Jinsei jerks wildly from social crisis to crisis at a pace that can at times feel like the spiraling scroll of a social media feed, a solitary scream into the void at the injustice of the world where no one will fight for change. What holds it together is that, even at its most unflinching and unrepentant, there’s a desire for something better, deep down. Even in this anger, there’s a brief hope that something could be better.

While the closest comparison point would be something like On-Gaku: Our Sound, another critically-lauded solo-animated venture, what this film does with the freedom of solo filmmaking allows it to stand out from that shadow with its own identity. Solo filmmaking is a liberty that allows the film to be critical and targeted in the ways needed for this story to exist that are often impossible in such a risk-averse industry. It’s thrilling and daring as a result.

There’s nothing like Jinsei being produced in Japanese cinema right now, whether by major studios or smaller indies. Suzuki takes advantage of his rough solo animation skills freed from the necessity of answering to financers to create a true indie wonder.

Japanese Movie Spotlight is a monthly column highlighting new Japanese cinema releases. You can check out the full archive of the column over on Letterboxd.