As this year’s Tokyo Game Show begins to fade from view, and the season of major gaming events around the globe comes to its conclusion until next year, much has been made as to the role of Japan’s premier gaming showcase event in the context of both the domestic and international games industry. With the demise of E3 and its replacement, Summer Games Fest, existing as a closed-doors, media-only and online streaming affair, many have looked towards Gamescom and TGS as the events that replace the former tentpole as the face of the games industry.

The reality, especially in the case of TGS, is different. To understand the role of TGS in this changing landscape, however, it’s worth considering what E3 was in its heyday, and why these modern events exist. What does Tokyo Game Show actually offer to its general audience?

E3 was never about the public

Why did the games industry band together to host the first E3? Primarily, it was to put forward a more positive face for the growing, influential entertainment companies in the sector in the face of growing scrutiny.

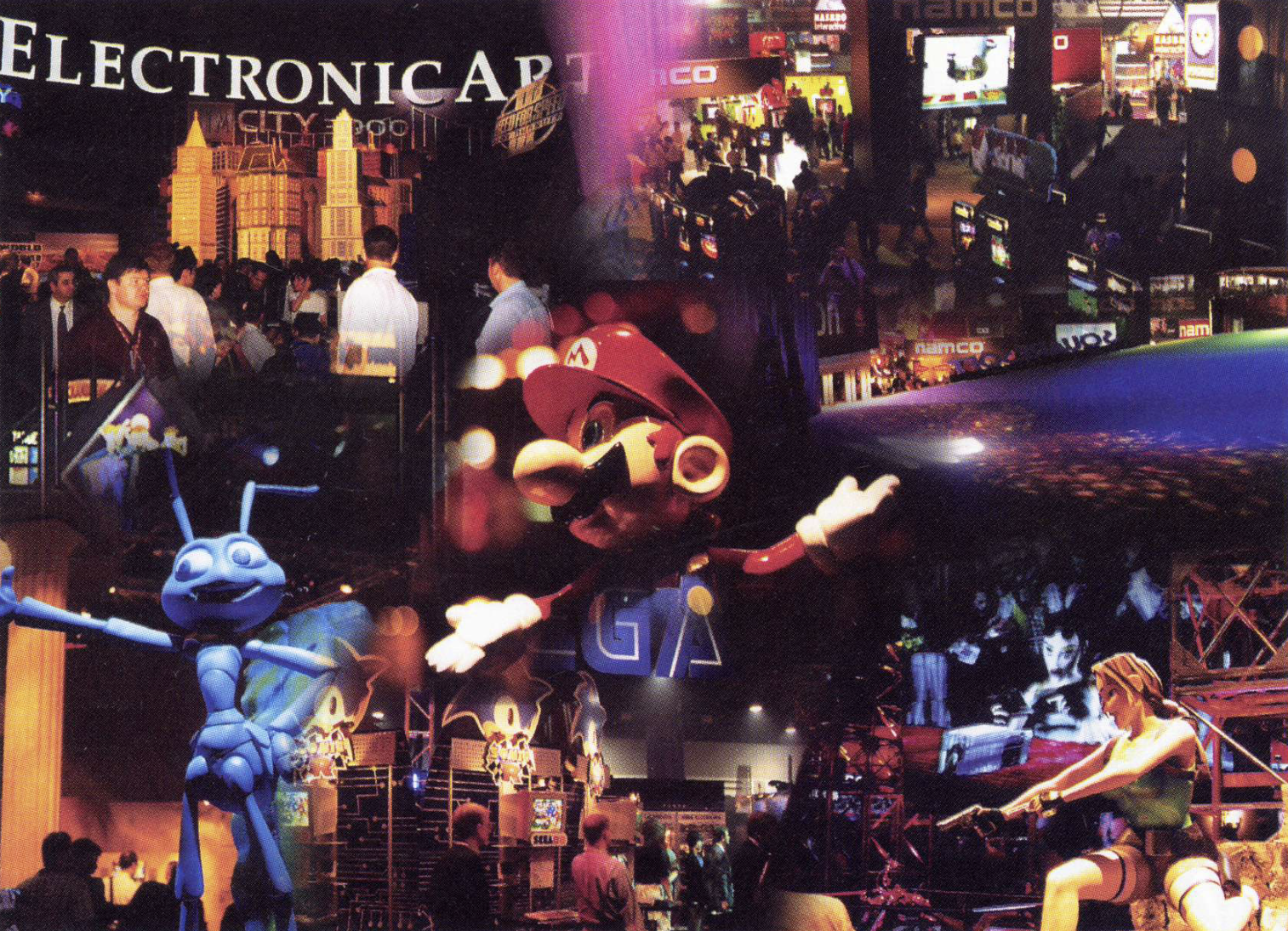

The games industry, while thriving off the backs of arcades that attracted scores of young people in the social third place of Street Fighter, Time Crisis, Donkey Kong and high school dates, on top of a burgeoning home console industry dominated by Sega, Nintendo, and the recent intrusion of Sony, was facing growing political pressure in the US. Just two years earlier, many of the major gaming companies were dragged before congress to answer questions regarding violence and explicit content in a growing number of major releases. Mortal Kombat’s executions were bloody spectacles, while Night Trap promised cheesy B-movie antics with a bit of raunchiness. Far from the only games to feature such content, they nonetheless became the poster children for what was seen as an industry out of control and in need of external regulation. Something no-one in the industry wanted.

This led to the creation of the Entertainment Software Association (ESA) and the ESRB in the US to stave off government intervention with the promise of self-regulation. This didn’t mean that the industry was in the clear. It was still very clearly a sector under pressure, needing to change the narrative and set the conversation for itself, rather than having external forces dictate its role. Thus, E3 was born.

It started as a trade show, not open to the public but with the hope of putting forward a vision of what games could be beyond the controversy, at a time when the industry was undergoing a revolution as 3D technology entered the home. In short, it was a chance to wash the industry’s name and promote its best face forward, the exponential growth in gaming transforming it into a festival that eventually the public were also invited to see for themselves. It aided the industry’s growth, and continued to exist because it always had.

Fast forward to the late 2010s, and the question many in the industry had, including those who helped scale it to the titan it had become, was simple. Is E3 even necessary anymore? While many just took it as a given, for participating companies, they were spending millions to share a spotlight when they increasingly wielded the power to act alone online or on their own terms by capitalizing on inbuilt fanbases. Companies like Ubisoft and Electronic Arts were already hosting their own public events in direct competition with the show by 2019. Even if these public single-company shows didn’t get the audience of an E3, they could avoid the same weekend or create a spotlight just for them, making them more memorable as a result.

For all E3 was viewed as an ideal by those who attended or had fond memories catching up with the announcements during its peak, the show was already feeling aged long before the pandemic put it to rest. But what does all this have to do with the role of Tokyo Game Show in the modern gaming landscape? For that, we have to understand the purpose of Gamescom as it grows from strength to strength as a public-first showcase of the future of gaming.

Gamescom

In 2019, the last in-person E3 before its permanent cancellation, in-person attendance figures stood at roughly 60,000. Meanwhile Gamescom, in Cologne, Germany, welcomed 373,000 people through that year's equivalent 5-day event.

Unlike the trade-first nature of E3, Gamescom has always been an event made for public consumption, designed to introduce the games industry to a fractured European region. It was a continuation of a similar event held in Leipzig, one which hoped to further establish the industry into a European industry which had always been historically more fractured than that seen elsewhere. In Eastern Europe, piracy through PC platforms was rampant, while you even saw a range of beloved European-only games consoles and PCs for which games would be developed for throughout the 1980s and 90s. The hope for the show was to build cohesion and increase awareness of gaming for what it is and could become. It was a representative for the European industry.

Its role has shifted and grown as an industry-wide trendsetter as it becomes the home for companies to announce new releases thanks to showcases like Opening Night Live. Yet in spite of this, the reason Gamescom was successfully able to return after pandemic shutdowns where E3 failed is the flexibility and ultimate purpose of the event itself. E3 was a trade-first event, and even when opened to the public, its location limited its scale. This was aimed at a market where public awareness and word-of-mouth was needed, and designed to bring as many people through the doors as possible as a result. It's possible nowadays to reveal a game in a YouTube video, but Gamescom is not about reveals and itself.

It was for everyone, and thus, it could become a vehicle for a marketing campaign and a word-of-mouth success story. With hundreds of thousands of attendees, a strong demo with great promotion can turn the tide of a game's success because ordinary people, not industry veterans are the ones seeing it. Which brings us to Tokyo Game Show.

Tokyo Game Show

America is the default for the games industry, especially with Sony having revised their business over the past decade to bring a US-centric focus to their PlayStation division. Gamescom exists to localize this industry and funnel its message for a European audience. Tokyo Game Show exists to represent Japan and give them a voice on the global stage.

The economics of the Japanese games industry are far removed from what we see elsewhere. It’s a market dominated by mobile gaming (with 75% of revenue coming from the sector according to this year’s Games Industry Report by event organizer CESA), but with a still-strong console market and growing PC sector. It’s also a country where Xbox’s continued slide into irrelevancy is only halted by a growing PC market and the slow intrusion of PC Game Pass in the region (even if this could soon be stifled by recently-announced price increases). Average wages are lower than the US thanks to a stagnant economy going back decades, and Sony’s decline with younger audiences in the region can be partially attributed to the company’s refusal to adjust prices to cater to spending power whereas Nintendo Switch 2, already attuned to the Japanese gaming scene through its hybrid nature, received a region-exclusive cheaper model to keep it affordable.

It creates the circumstances for an industry that isn’t represented in global showcases at Gamescom or Summer Games Fest, even if some of these Japanese companies like Square Enix and Capcom make their presence felt at these events. Even then, some of the titles from these Japanese titans are resonating to a greater extent globally rather than domestically, due to the growing cost of new releases. With luxuries the first thing to go, people will just buy used games for cheap from second hand stores or ignore a console entirely if the cost of entry is too much compared to the Switch or phone they already own. This is why according to that same survey, amongst Gen Z players, even the Nintendo DS is a more popular console than PS5.

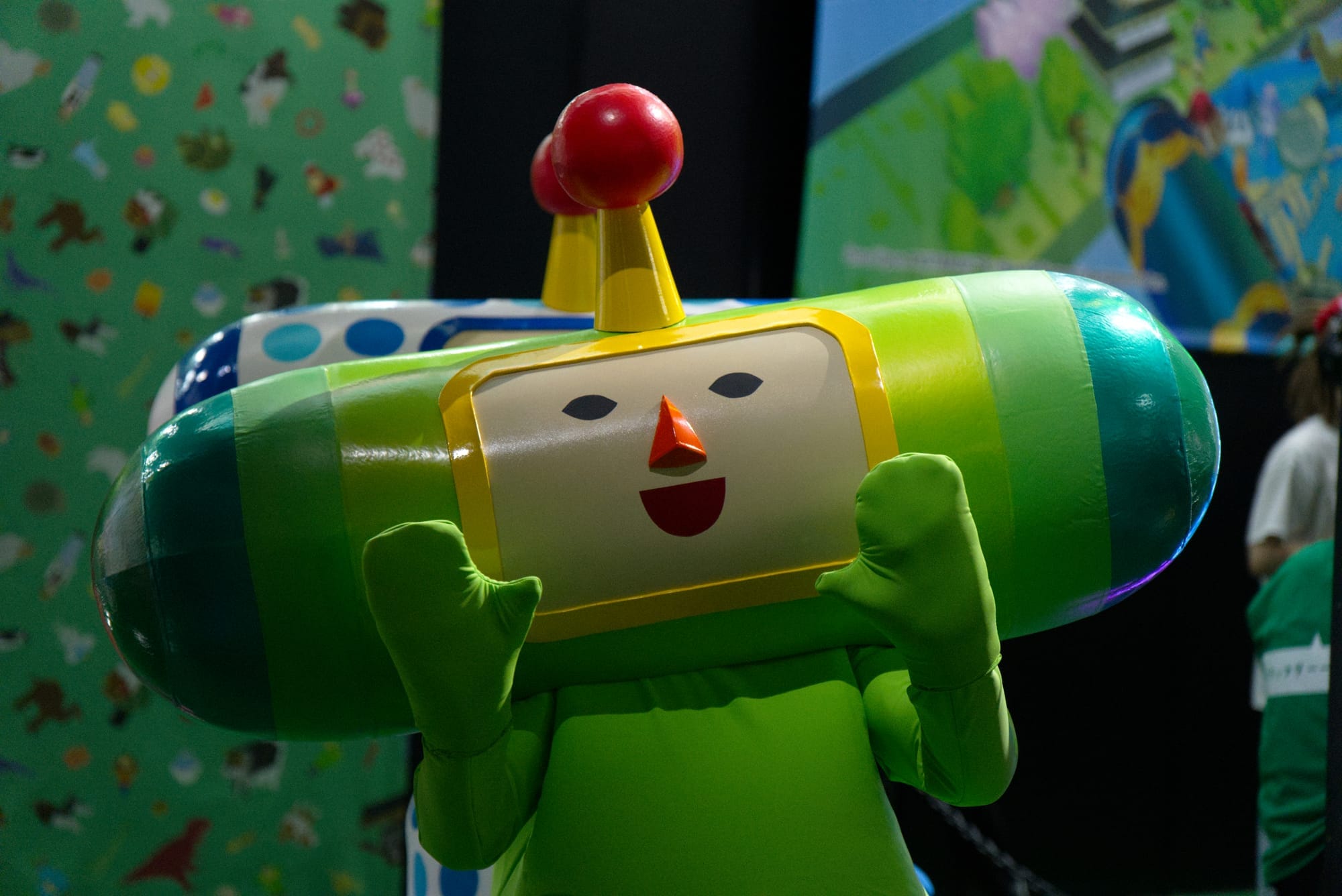

Tokyo Game Show is designed to thread a needle between what Japanese players could be interested in, and an event that caters to the interests of a vastly different market and dynamic simply not represented elsewhere. One that loves mobile games but cares for consoles, and seeks a different sort of game to that desired in the West. It, too, is a public-first perspective similar to Gamescom, but above all else, it exists to help showcase what Japanese players are interested in and provide a space for the industry here to represent itself accurately to both domestic and international audiences.

Which made this year’s Tokyo Game Show a somewhat awkward event, in many ways. Many look to Japanese games for their creativity and originality, yet recently 51% of devs admitted to using Generative AI tools according to the recent 2025 industry report, and the event marked this revelation with its own AI Technologies Pavilion. The strength of mobile gaming has allowed new players to rise such as Cygames, but the predatory nature of its microtransactions and gachas in some of the industry’s more extreme titles has led to almost one in five players admitting to prioritizing in-game spends over rent.

If you attended this year's Tokyo Game Show, you would find an event dominated by upcoming free-to-play mobile games, either from domestic creators or inspired by Japanese culture from companies across East Asia. With how dominant such titles are, it's not inaccurate to see them so prominent. Yet whereas the event usually curates its showcase to put the best face of the Japanese industry forwards, it seemed to fall short in this respect. Last year was the year of Death Stranding 2 and major showcases from big publishers, but also startling creativity by smaller developers across the industry. This year, the burgeoning independent scene only growing from strength to strength got kicked out of their usual show floor presence to a side corridor because of the AI presence at the event.

What can be said, however, is compared to the media-focused Summer Game Fest and Gamescom, is that there isn’t an event like Tokyo Game Show in the global calendar. Even with these flaws, domestic publishers who wouldn’t have the ability to showcase internationally still could make their presence felt. It was a chance to play games like Yunyun Syndrome!? Rhythm Psychosis and Tiny Metal 2. Last year, it introduced me to titles like Noroi Kago. Publishers like Room6 and Playism are able to make their presence felt at indie-focused events like Bitsummit, but their presence here allowed them to put themselves forward at an event where the eyes of the world were on them. Even in a more middling year creatively, this show had a home for otome games, mobile games, console games, indie games, and everything in between.

Tokyo Game Show is the face of Japanese gaming, often for better and for worse. And for an industry where much of it can be overlooked beyond the big names of Nintendo and Sony, that matters.