By 1945, it was clear that Japan was going to lose in World War II. The general population, however, were kept in the dark, even if many suspected this could be the case. The war effort domestically, thus, continued unabated even as rations and life for domestic citizens became increasingly dire. While the government were responsible for the war, many of the citizens became victims of powers far beyond their control. Cocoon, based on the one-volume manga of the same name by Machiko Kyo, is a recently-broadcast anime special from Sasayuri, a studio founded by Ghibli alumni and based on the real-life tragedy of the Himeyuri students in the closing stages of the war.

Notably, alongside being their first solo project, this is a cross-generational project matching veteran ex-Ghibli talent like Hitomi Tateno (animation director and producer on the film) with newer faces like director Yukimitsu Ina, alongside well-known creatives such as Kensuke Ushio, whose minimalist but caring music choices bring sharp focus on the tribulations and pain these girls face.

The Himeyuri students were sold a lie in return for co-operation in the dying stages of the Japanese war effort. Promised an easy Japanese victory over American forces invading the Okinawan peninsula, they were told they would go from occasionally helping reconstruct bombed buildings and other tasks alongside an otherwise-normal school life to assisting in hospitals ‘far from the front line’ on a temporary basis. Then, they would return to school.

Instead, they were sent to the front lines, many dying from bombs and gunfire they faced from enemies while being mistreated and raped by their own military in a hopeless fight where few survived. Worst of all, when the Himeyuri students were relieved of duties, they were abandoned. Go home, they were told, but they were given no assistance in doing so. Many committed suicide.

While not to suggest that no media exists that portrays this war as justified from sectors of Japanese media, or that there weren’t people then or now that attempt put a sympathetic lens on atrocities inflicted by the Japanese military against countries it occupied or the enemies it faced in battle, many condemn the war while recognizing the betrayal by officials and victims who suffered most at home. Beloved works like Barefoot Gen and Studio Ghibli’s Grave of the Fireflies showcase this dichotomy well, as have other anime and live-action drama throughout the post-war era.

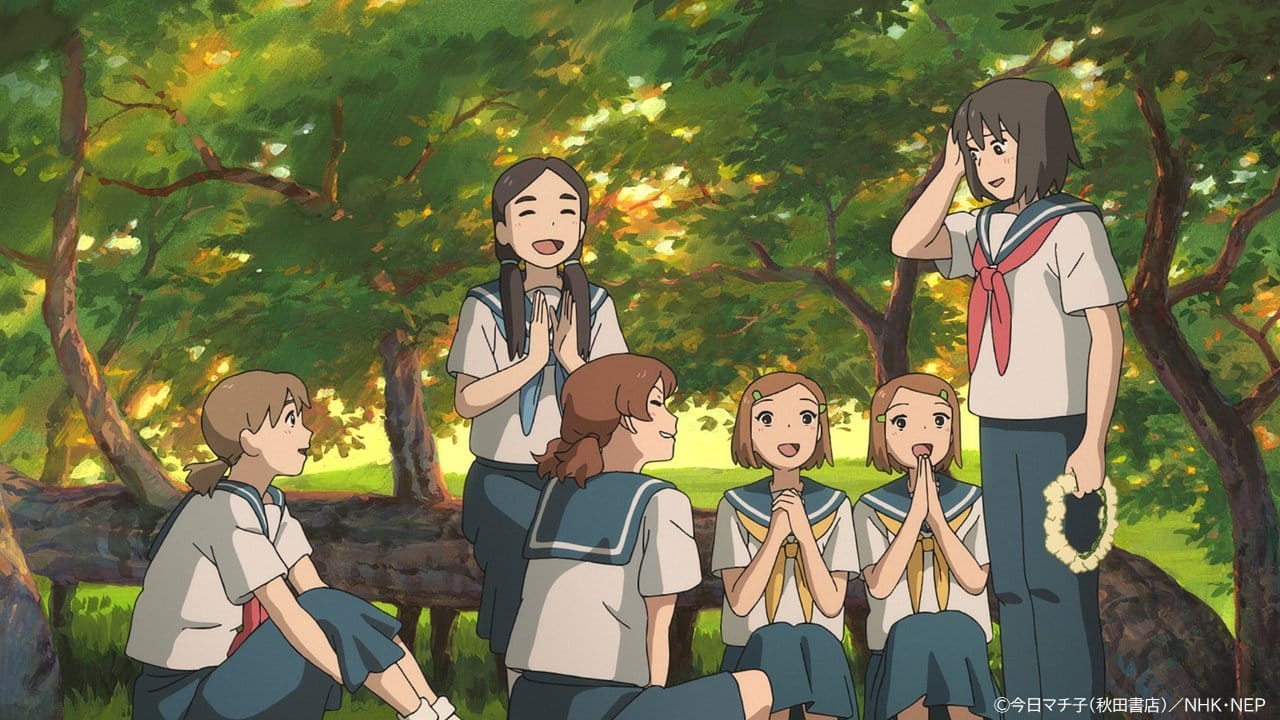

The purpose of this new anime commissioned by NHK is to mark 80 years since the end of war while shining a light on an oft-overlooked atrocity. The series follows a class of roughly 30 girls, representative of the hundreds of Himeyuri students sent to slaughter and what they witnessed in their hopeless campaign. Particularly, the story centers on the friendship of San and Mayu. They’re very close, sharing everything together as they each try to survive. The news they’re heading off to war is met with positivity by them and the entire class, if not overwhelming excitement. They can contribute further to the war effort this way, they think.

What was unique about the atrocities faced by the Himeyuri students, and this story amidst a litany of other war media, was the gendered nature of the suffering inflicted upon these young girls. Rather than risk the lives of boys who could join the conflict, girls were sent to the front lines because their losses were deemed lesser. Their innocence was an asset, not a liability, in the eyes of the starved soldiers facing death head-on with nothing left to lose.

Cocoon’s power comes by centering on this gendered violence through the eyes of San and Mayu. Their close relationship often flirts with the romantic as they’re brought together in their strife, but above all else portrays a platonic protective care for one another. They would do anything to keep the other alive. Their love for one another is a harsh contrast to the callous world around them.

One key decision made by Kyo while writing the original manga was the choice not to give defining facial features or designs to the Japanese soldiers of the war, impacting onto the story a clear distinction that this is not their story, and that their existence was even a threat to the young women tricked into this dire situation. While care is given to focus on the tarnished clothing of the young girls as it becomes increasingly-blood-stained from their treatment of dying soldiers, the most focus we get on the soldiers themselves is their nonchalant view of war as anything but a game with a victor, and how little they view the girls as people.

It makes for difficult viewing. Compared to the somewhat-peaceful lives of the girls prior to their deployment, no moment is safe. A conversation reminiscing on the final days before their new reality is interrupted by the sound of an explosion and the need to bury their friend. Even as they get a rare moment of rest, recovering soldiers will prey on the girls, as we witness in all-too-uncomfortable if tastefully-obscured reality.

It becomes almost too much when the news they’ve been abandoned by the government reaches the girls. Caught in the crossfire of both sides, their blood spills, yet rather than pouring out of their corpses a dirty red like the men, it renders as beautiful flowers. At least in death, the girls regain the peace of the fields they once enjoyed.

This is a story seeped in metaphor. Cocoon, itself, refers to the silkworm the girls often bring up in conversation, and the beauty that comes with a maturity they will never get to reach. Of course, silkworms are often cared for by men until they reach maturity, only for those same men to harvest their silk and kill them, a fate not dissimilar to their own. While it’s no guarantee of survival, it’s possible to accept this fate or walk away from this cycle. Perhaps that beauty can endure by choosing life, even while facing death in the face.

Although this story has previously been adapted as a stage production, it’s hard not to feel that animation is the ultimate vehicle for bringing this story beyond the pages of the manga to a wider audience. Cocoon is damning towards the powers that allowed these events to happen but determined to respect those that died. While this anime can feel rushed and awkwardly paced in places, restrained by its TV broadcast and limited runtime, through the story’s grounding in San and Mayu’s relationship we are brought into the trenches of their hopeless fight to survive with equal love and anger.

I’m glad this film exists, and can only hope it reaches a wider audience. If only to ensure their memory lives on for the next generation to learn the lessons of the past.