A small class in a rural town on a small island far from the mainland of Japan and broader civilization. A place steeped in shared tradition, but also somewhat insulated from the grander changes sweeping the country in a period of great uncertainty. At least, for a time. As everything changes, an older figure who can put on a brave face in the face of an impossible situation and that can be relied on for safety means everything to a kid dealing with the impossible.

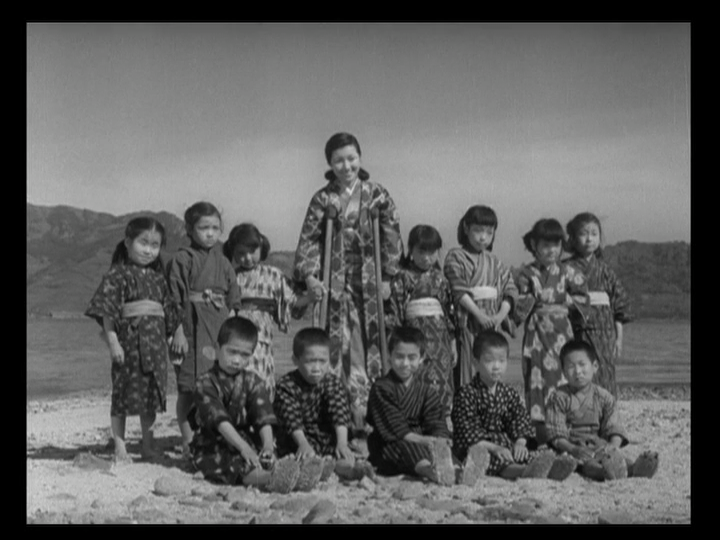

Keisuke Kinoshita's Twenty-Four Eyes is an initially unassuming film, though anyone sitting down to it for the first time will immediately take note of the sweeping 20-year period for which the story is set. It begins in 1928. After the old teacher of the school retires, a younger woman named Hisako Oishi (played by Hideko Takamine) comes to the island of Shodoshima to teach the incoming class of first-grade students. She’s an unusual sight to those living on the island: she rides a bike, she wears a Western-style suit when everyone else wears more traditional Japanese clothing, and it makes even the older villagers nervous to her new ways. Over time, through classes where she sings, plays with the kids and slowly teaches them new skills, her young students begin to appreciate her presence even as the adults remain uncertain.

Over the next two decades we witness the changing lives of this village and for Oishi herself as the world transforms and Japan’s imperial expansion encroaches onto their rural life. In that time World War II begins, then ends. Oishi teaches her class, full of ‘small and anxious’ eyes that she never wants to lose their sparkle. Only then to watch those kids grow and mature, and watching them go to fight in a war from which they may never return.

There’s beauty in the world because we are alive, and in hardship it is this beauty and goodness we must remember to ever hope for a brighter future. Following Japan’s surrender in September 1945, the country spent seven years under the occupation of the United States. In that time the US military enacted a number of reforms, including dismantling of the wartime government and enforcing a new pacifist constitution upon the country. Intense censorship over the Japanese media landscape was enacted, though this was less about allowing free discussion and more about shifting the propaganda of old towards a new era censorship promoting American narratives and the post-war (and Cold War) new order.

With strict control over the flow of information, there was little opportunity for the Japanese people, themselves victims from government-mandated misinformation, widespread famine in the later years of the war, and the loss of close family sent to fight wars many didn’t support, to reflect on their own experiences of war. Much of the media messaging during this era of censorship was far more focused on enacting punishment and seeking blame than allowing people to share their own stories of sacrifice and suffering, or to grieve.

As the American occupation came to an end following the signing of final treaties in 1952, Japan returned to self-governance with the end of this enforced censorship. The years which followed saw a number of stories released by authors and filmmakers that sought to make sense of the last decades and what it meant to have lived and lost fighting for a lie.

Twenty-Four Eyes was adapted from the novel of the same name by Sakae Tsuboi, first published in the months following American withdrawal. The movie released in 1954, chronicling the lives of a generation of students and their teacher Oishi amidst the subtle, then blatant, intrusion of fascism on a rural community otherwise disconnected from a broader Japanese society. Their isolation on an island leaves them so far adrift from mainland trends that the idea of someone in Western clothes and riding a bicycle, or even having a teaching degree, is suspicious enough to be adversarial until they can prove they’re trustworthy.

These are people connected more by proximity and community spirit than any sense of nationalistic flag-rallying war fervor. Why should this small community even care for a war elsewhere?

Yet the poetic tragedy of the film comes from the creeping inevitability of actions by the Japanese government that are as devastating as they are inescapable. When we meet Oishi’s first class in 1928, these are innocent kids with the limitless possibilities of the world on their shoulders, singing about trains that go choo-choo down the track. In her they find a teacher that inspires them and they adore.

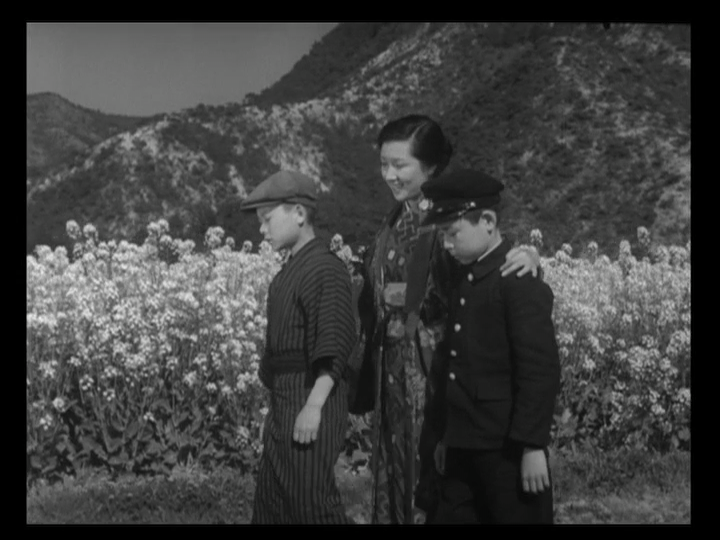

By 1933 she’s getting married, and this class still want to see her on this auspicious occasion. They want to meet the husband, because this new partner must meet their expectations if they’re going to let ‘their’ Oishi get married off to some engineer. A teacher who can inspire and broaden your horizons far beyond the lessons you learn can be a role model who sticks with you long into adulthood, they’re inspirational. Those are the stories you tell your kids and grandkids, the memories they will want to pass on to the next generation.

But things are changing. Casual conversations are overshadowed by knowledge of invasions in Manchuria and Shanghai, and banners proclaiming the glory of the Imperial army. Teachers are being investigated for seditious material, but is there really anything subversive or dangerous about the hopes and scratchings of children? The kids now want to fight, too, not play.

No one in this town is saved from this creeping control over speech, even as the authoritarian encroachment does nothing to deal with the real problems these people face far from the pointless wars being fought elsewhere. The tribulations of family, and the patriarchal society that can rip the hopes and dreams from under someone under the expectations of assigned jobs and roles, are far more worthy of fighting for justice than any military campaign of the era. It’s hard not to see hope for the future disappear under the weight of the precarity befalling everyone, leading to increasing disillusionment that the idea a better future will ever be realized.

With inevitability and responsibility bringing an end to their youthful innocence as these kids are forced to transition from adolescence to adulthood before their time, you begin to question whether it's worth giving these kids hope in the first place. Then we remember. In our greatest pain and deepest struggles, we remember the inspiring figures of people who changed our view of the world, even for a moment, or taught us to see the world differently. For those twenty-four eyes, Oishi was one of them, and as the dust settles, those who remain return to see that inspiration.

Twenty-Four Eyes endures today as one of the ultimate stories chronicling wartime life, and a classic amongst early-postwar cinema seeking to reconcile Japan's role in World War II. This is a film that explores encroaching wartime fascism and watches as the hopes and dreams of young kids are crushed by society and fighting that tragically consumes what once was possible for these wide-eyed youths. It endures because in its humanistic view of this turbulent and ever-changing era, it captures the hopeless inevitability of this suffering while highlighting the memories that, after it all, endure.

For those watching it in a post-war world, the film was a chance to collectively grieve for the lives they lived while reflecting the warmth of the teachers and people who shaped them. All while bestowing a morality and desire for peace that has fueled post-war Japan ever since. It’s relentless and shattering, but it reminds us of our humanity amidst national suffering. Both then, and now.

scrmbl's Classic Film Showcase shines a light on historical Japanese cinema. You can check out the full archive of the column over on Letterboxd.