Some bands last for decades but don’t shape much of the sonic ecosystem around them. Other times, a group exists for just a few years but has a massive impact reverberating even into today.

Flipper’s Guitar existed for less than five years, but the pair of Keigo Oyamada and Kenji Ozawa shaped an entire decade-plus of Japanese sound. Starting out as a British-indie-rock-obsessed outfit, the duo gradually turned to music offering a sonic and historical pastiche, full of samples and references to the global mish-mash of favorites they had.

By the time they suddenly called it quits in 1991, Flipper’s Guitar helped pioneer a new sound that would define the decade ahead — Shibuya-kei.

The two primary members of Flipper’s Guitar would both go on to have even more celebrated artistic careers, but to understand the paths Oyamada and Ozawa took, you have to start with the group that turned them from privileged music geeks with a C86 fascination into stars…and the architects of the unstuck-in-time sounds of Shibuya-kei.

Fire The Tricot

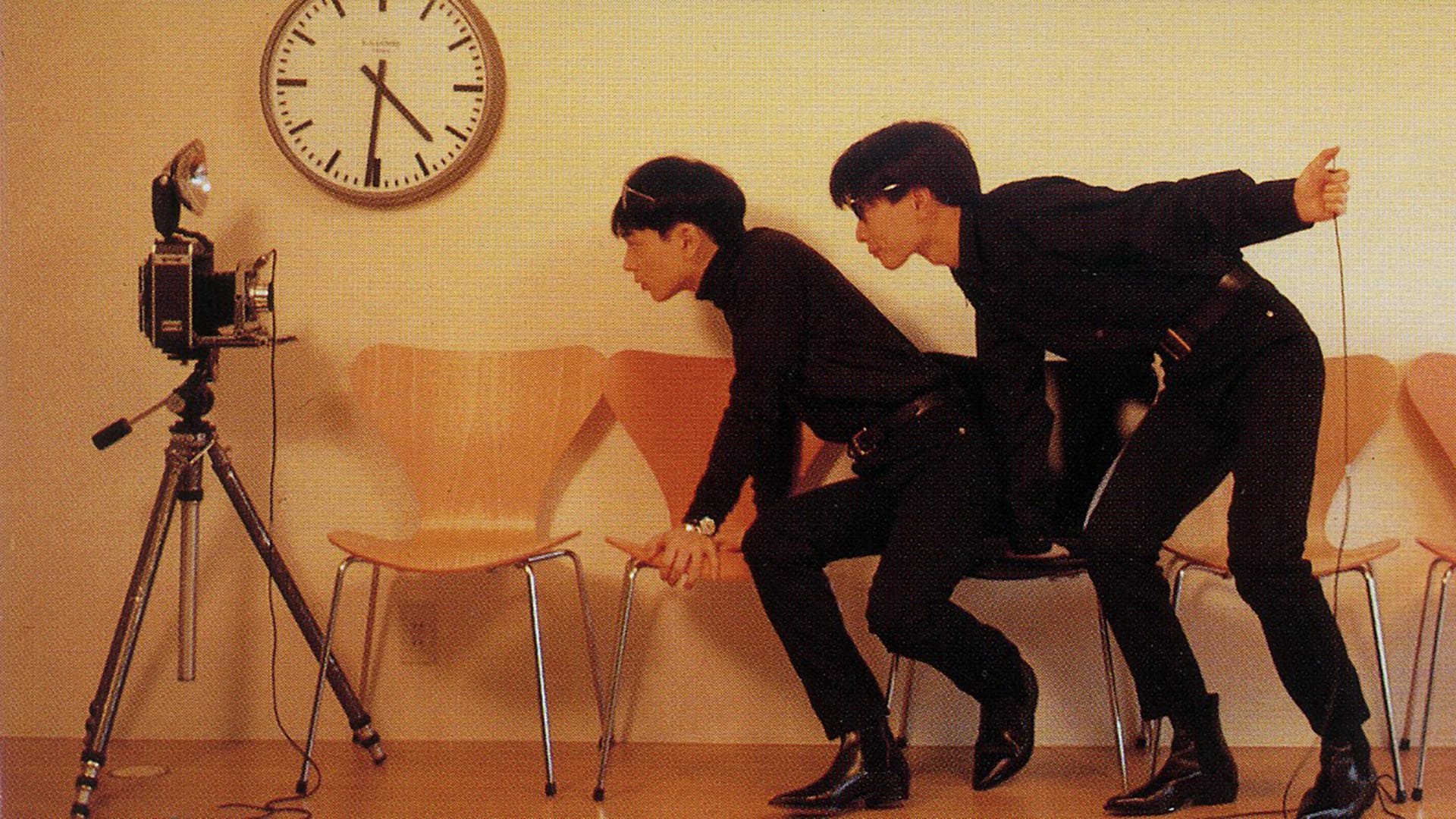

Oyamada’s first musical project was a band called Pee Wee 60’s, an outfit dabbling in the then-fresh sounds of British indie-pop ala Orange Juice, Aztec Camera and the like (check a rare 1987 recording of them live above). The lineup changed shortly after its formation, topped off by the arrival of Ozawa, prompting a name change to Lollipop Sonic. Under this new guise, the group kept playing Euro-indebted rock but with a growing splash of ‘60s touches that added a retro color to it.

Found by one half of proto-Shibuya-kei band Salon Music, the group landed a major-label deal albeit with one more requirement — they needed to ditch the Lollipop Sonic name. As would become common for the band — and detailed by writer W. David Marx at length in his essential dig in the history of Shibuya-kei — they opted for something referencing a British band they liked, in this case the dolphins appearing on the cover of an album by Scottish rock group Orange Juice. That UK outfit also inspired the name of its first full-length album Three Cheers For Our Side ~ Umi E Iku Tsumori Janakatta ~ released in 1989.

Composed primarily of material developed during the Lollipop Sonic days, Three Cheers hinted at the sonic diversity the group and its two primary members Oyamada and Ozawa would go in the years ahead. Nestled between jogging indie-pop celebrations of youth and trendy drinks, Flipper’s Guitar dabbled in tropicalia, bossa nova and older forms of global pop. It’s a record overflowing with references to the bands they love and capturing a similar English adolescence vibe (complete with all English lyrics), with the best moments finding them wrestling with the fact youth is nearing its end (“The Chime Will Ring”). While bogged down by indie-pop cosplay, Three Cheers pointed at potential.

Which would be great for an actual indie band looking to make strides, but Flipper’s Guitar was with a major. This album sold poorly, necessitating a shake-up.

Young, Alive, In Love

The exact reason why three members left Flipper’s Guitar isn’t clear — Marx shares two theories, one about the label wanting to shift focus to Oyamada and Ozawa, the other that working with these guys was just too tough — but the five-piece outfit turned into a two-piece. The sound changed too, at least a little. They sang in Japanese now, and while they were still up for shining light on the assorted anorak crowd that influenced them (a song called “Haircut 100”), the songs appearing on sophomore effort Camera Talk explored a far wider world of influences and, in some cases, direct inspiration.

Here’s where Flipper’s Guitar truly becomes a foundation of Shibuya-kei.

The duo dig further into far-flung sounds, with more explorations of bossa nova and Euro-born cafe cool. Electronics start squiggling up on the title track, while “Big Bad Bingo” features a flirtation with the then-on-point Madchester sound (something that would loom larger soon enough). There’s a touch of American country twang to “Cloudy (Is My Sunny Mood)” while “Cool Spy On A Hot Car” draws from the soundtracks of old espionage films. So does opener “Young, Alive, In Love,” with its opening stream of voices being shaped by Italian film…specifically the start of 1965’s Seven Golden Men.

That song, Italian inspiration and all, proved to be Flipper’s Guitar’s big breakthrough. It served, kind of ironically given its theme-song origins, as the opening for the TV drama Yobiko Boogie, helping put it in front of a new audience and leading it to the Oricon Charts. Oyamada and Ozawa became something akin to idols, albeit ones with a deep interest in the early era Creation Record’s stable of artists. This is also when they started getting grouped with Pizzicato Five and Scha Dara Parr in the nascent “Shibuya-kei” movement, a title created by the media reflecting where young people were buying these artists’ records.

Flipper’s Guitar had one more pivot ahead…and one that would go even further to defining just what this nascent scene was.

Groove Tube

Homages to artists the members of Flipper’s Guitar loved were always a staple of the band’s work. On Doctor Head’s World Tower, they take that fandom further by sampling a kaleidoscope of famous works, made almost brazenly clear in the full-length’s opening moments as a bit of The Beach Boys’ “God Only Knows” plays.

What follows is part attempt to ride the Madchester vibes laid down by the likes of The Happy Mondays and Primal Scream, made up of samples galore and a shift towards dance sounds absent from the pair’s first two albums. “Collage” isn’t quite right as at its best they reveal new angles on familiar sounds and at its worst appears to be straight copying (a point Marx and many others have rightfully dinged them for). It’s highs though — the bounce of “Groove Tube,” the trippiness of “Aquamarine,” the multi-part dizziness of closer “The World Tower” — not only helped underline what Shibuya-kei would become, but offered a preview of where both Oyamada and Ozawa would go as solo acts in the years ahead (in particular, World Tower feels like the first hint of what would become Oyamada’s masterpiece Fantasma later in the decade).

Folks wouldn’t need long to see just what those two would get up to alone though, as Flipper’s Guitar broke up suddenly in 1991, for undefined reasons. While the band’s label would try to squeeze more out of the band with a best-of compilation, Oyamada and Ozawa were off on solo careers, and Flipper’s Guitar was now part of the past…but one helping to shape the sound of an era still unfolding.

Five Essentials

“Goodbye Our Pastels Badges”

On the one hand, this is almost essential background information to understanding Flipper’s Guitar, as it overflows with references to the ‘80s UK indie-pop scene, including right in the title. Yet what separates it from the other fan-writings-turned-song is the pang of transience underneath, with Oyamada’s lyrics hinting at an awareness that the songs and styles that defined youth can’t last forever.

“Young, Alive, In Love”

The duo’s big hit, a number now conjuring up images of the dying days of the Bubble era and an all-around bright cut. Earns extra points for being a great example of what would define Shibuya-kei — it’s ear-grabbing opening scat is taken from Italian cinema.

“Camera Full Of Kisses”

There’s some alternative timeline where Oyamada and Ozawa decide the mainstream spotlight wasn’t for them and they wanted to keep on living in the eternal jangle of ‘80s UK indie-pop. Songs like “Camera Full Of Kisses,” an example of how good they could do that style, probably would have earned them tons of cred from the global twee underground.

“Big Bad Bingo”

Flipper’s Guitar meets the dance floor for the first time, which helps shape…

“Groove Tube”

Almost certainly owing to all the uncleared samples crammed into it, you can’t easily listen to Doctor Head’s World Tower officially. Hunt down the CD, or get creative! “Groove Tube” is one of the only numbers from Flipper’s Guitar’s third album easily accessible, but that’s not why it ends up here. Rather, it’s one of the best mergers between the project’s indie-pop roots and its Madchester phase, both perfect for 1991 and showing where Shibuya-kei mish-mash could go.